“What the fuck happened in Creggan?”

It obviously wasn’t a question uttered only by Derry accents on Friday morning but perhaps only a Derry response could help encapsulate the numbness in the city to the aggressive resistance of occupation and what is now 50 years of fighting against British policing.

“They were just rioting, having a bit of craic, then someone ruined it.”

In her Irish Examiner piece, Aoife Moore described a riot in the north as a pastime option in blackspots of the Troubles and, when you step back and consider that any place could pass off violence in the street as anything within the boundaries of not going too far, you get an insight into the psyche and the history of the people of Derry.

Like a lot of the culture in the maiden city, you’re just born into it and know or want for nothing else. You wear a Celtic top but never in the Waterside. You speed up at the amber lights in Newbuildings before you’re brought to a stop because you’ve learned, not through experience, to be wary of places with a red, white and blue footpath. You take on a way of life that you don’t even realise is so far within its own little bubble that you draw comfort from the fact that the other half of the population would feel intimidated coming into your area – one manned with tricolours and Brits Out graffiti – because you felt the same way in Newbuildings. But you’re at home here. You even feel safe.

And, before the polling stations open for election, you join the rest of them. You wheel a trolly around – there’s always a trolly – and you collect things that will be chucked at the bulletproof Landrovers when the police come around on voting day. You don’t know why anyone’s doing it, some of them are simply looking to be chased, for the thrill and badness of it – a cheevy, as they say – and the rest, at least most of them, are doing it because this is just what they do.

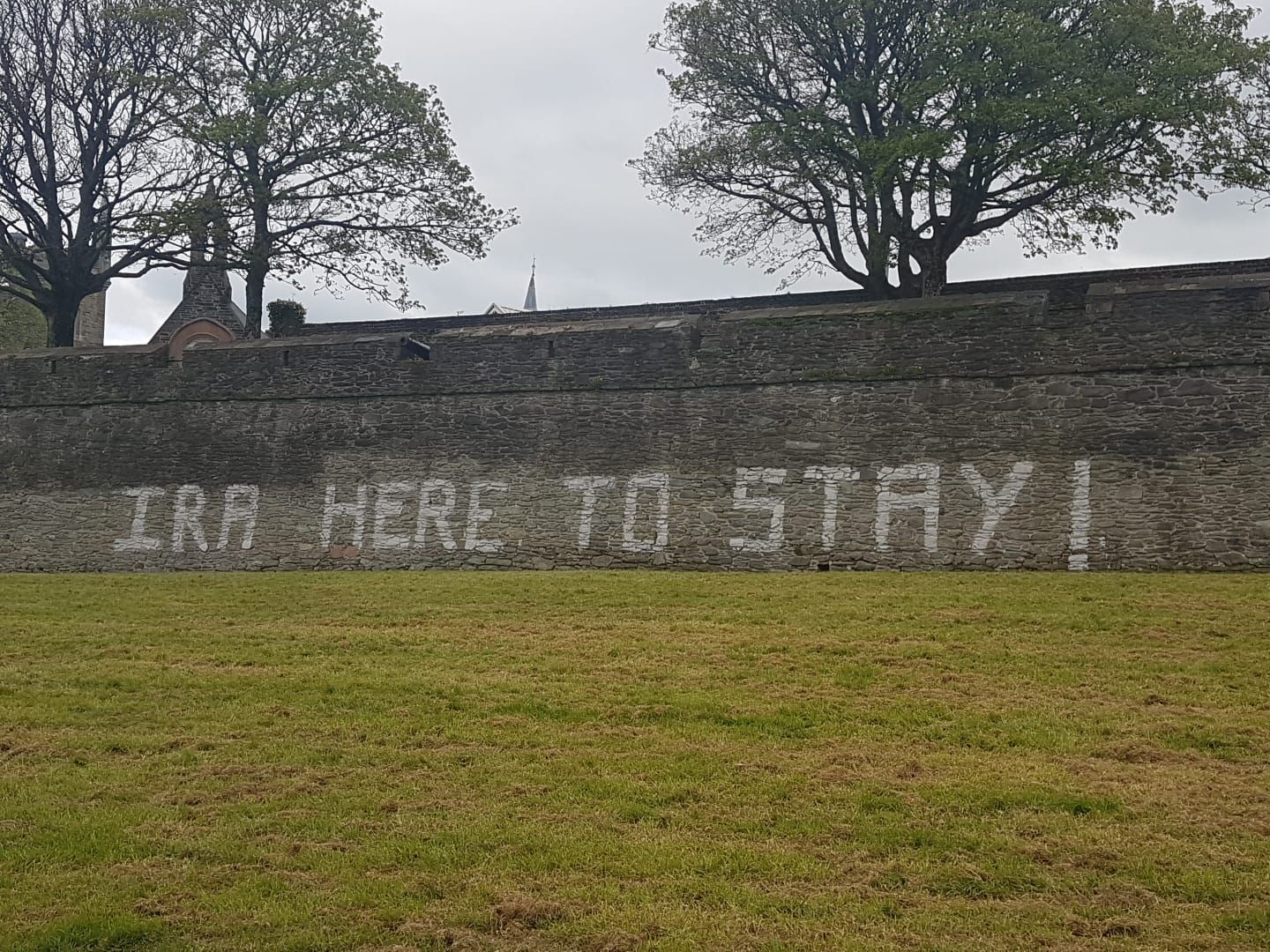

Some people spray IRA onto a wall as flippantly as Declan Rice posts Up a Ra on social media and, for others, throwing stones at the police is a raison d’etre, more so out of legacy issues than any concrete ideology.

Whilst it’s a generation that’s known relative peace and one that has basked in the tranquility of the Good Friday Agreement, they’re all still just a parent or an uncle away from knowing loss too, and they might’ve even seen brutality in action as children. But it’s also just that culture. You grow up convinced that a flying Union Jack is a threat to your existence, that whoever is driving the Landrover is an enemy with an agenda and that your turf is exactly that: yours.

You grow up thinking a riot with the authorities can be passed off as a bit of craic and, for someone who’d never engage with that fight against police forces, it’s frightening how much you can still get caught up in the normalisation and even justification of it. For someone actively involved in those physical encounters, it’s an easier infiltration to enlist them with a bigger, more serious, more dangerous cause – even if they were only doing it it in the first place because everyone else was. Even if they only thought it was a bit of craic.

In Creggan, the graffiti is suddenly a feature that your eyes are opened up to again.

The reality is that a lot of these engagements can be started with a group of 12-year-olds throwing stones at an armoured car. They don’t know why but they definitely don’t know why not either.

Unfortunately, the starker reality is that it’s only when a complete idiot decides to escalate the situation to levels of the reckless atrocity at the time of the Troubles that you really look again at the messages greeting the young people at heart of Derry every day.

‘Join The People’s Army’, it reads on a lamp post overlooking the bustling football pitches of Bishop’s Field and the new park where the youth of Creggan play in the stretching sunshine light.

On another day, you’d be guilty of looking right through these endless calls to arm plastered around Derry’s busiest residential estate but, in the wake of the murder of Lyra McKee, you see every last bit of both subliminal and unashamed indoctrination targeting the next generation.

The massive text in white paint running for the guts of a hundred metres up that steep Southway road implores the local youngsters to join Éistigí (they weren’t as conscientious with their spelling as Gaeilge), the youth wing of Saoradh. In such a focal point at the mouth of Creggan where so many visitors to the town will park their cars and walk down to the Brandywell stadium, they’re confronted with ‘JOIN IRA’ graffiti as their first impression of Derry and, all throughout Creggan, from the site of the old St. Pete’s school – now, more houses in its place – as far over to St. Joe’s and Rosemount, propaganda is rife.

‘End British rule’.

‘Reclaim your communities’.

Flags of the 32 County Sovereignty Movement wave in the wind above warnings to the RUC, dissolved in 2001.

Generators, garden fences and gable walls at the side of homes are a colourful mixture of markers and spray paint, murals and billboards and they carry an eclectic array of advertising for the like of the INLA, the RAAD and others have support weighted with ultimatums on behalf of the POWs, the prisoners of war.

If you were seeing this for the first time, you’d think it’s crazy and maybe it is when a direct result is open fire being shot at police and bringing an end to any life, not just one that was so full of passion and impact.

You’d think you had walked right into the heart of a war zone if you weren’t so numb to the madness of it all and that’s exactly what it is for some people still. A contested territory.

Before his fight with Floyd Mayweather, Conor McGregor had a profile pieceon his upbringing written by the legendary Wright Thompson of ESPN. It was an exciting, extreme, probably embellished picture of his life and of Crumlin life but it drew widespread criticism in Dublin because of how deadly and chaotic the area was made out to be for a global audience to read. It’s hard to say that Thompson took liberties though, or even exaggerated. It could simply have been a case of a man from a different country landing in Crumlin for the first time and talking to the locals about the gangs, the drugs and the fights. He was being shown grenade marks and pointed out where the divide was and where you shouldn’t go and, if you were never exposed to that place or that story before, the American’s dramatic retelling of it all could genuinely have been his thinking that it’s just wild country.

With a fresher eye and heavier heart, the graffiti, the flags, the slogans and images decorating Creggan make the place feel like it’s stuck in a time warp and if tourists think that the murals in the Bogside are interesting, they should walk up to the top of that hill where they’d get an authentic, current-day insight into the Troubles, half a century after they broke out and ripped the north apart.

To be honest, I always felt uncomfortable about those defiant statements that are made just hours after a tragedy has befallen a town. People are killed and it seems like a rush, even if it’s with good intentions, to show that whatever city we’re talking about won’t be brought to its knees. I understand the sentiment and maybe it’s a powerful message but someone is dead and I generally think it best to let the family grieve and be respectful of that for at least a few days before we’re told that we’re all going to stick out our chests and just get on with it.

When the love for Derry started pouring in, my initial thought was ‘piss off’. This isn’t the time to be pointing out how great Derry is or how friendly its people are because Derry is the place that allowed this fire to be fuelled and Derry is the place where Lyra McKee needlessly lost her important life. Now, Derry will forever be synonymous with her family in Belfast as the town that took her in her prime in exhange for a damned apology from the IRA who used the same statementto the Irish News to peddle their reasons for violence.

But what Derry has done is reacted.

The opposition were told to beware of the risen people but the majority of the town has risen in direct response and they’ve risen as one.

‘IRA are done’ is now what oversees the Creggan shops where the teenagers gather. A brave act, a powerful statement.

The dissident murals in the Bog’ have been x’d out and the town has spoken together that this ‘deployment’ against ‘British forces’ are ‘not in my name’.

When the first rally was planned after the shooting, BBC journalist Ciaran O’Neill saidthat it shouldn’t be the same voices and politicans on stage. “We need to hear from young people and friends of Lyra’s. Their voices will have much more of an impact.”

What has happened in the following week has sent shockwaves through the town and country. Lyra’s partner Sara led the way with that heartbreaking speech in front of a huge crowd that turned out to condemn the murder, and her friends followed her in a show of proper courage and genuine defiance by dipping their hands in red pant and leaving their marks in memory of Lyra on the office of a Dissident Republican group.

At the funeral, Father Martin Magill looked Arlene Foster, Michelle O’Neill and Mary Lou McDonald square in the eyes and asked “why in God’s name does it take the death of a 29-year-old woman to get to this point?”

There might be no-one standing in Stormont at present to affect change or to be the voice of the divided communities but the people of Derry are taking their own stand in the absence of any tangible help from its politicians.

Above the Free Derry Corner, planted across the famous Walls looking down on Fahan Street, it still says that the IRA are here to stay. The slogan can be seen as far up as the top of the Brandywell and from the bottom of Creggan and it’s there in the skyline looking out from anywhere along the Lone Moor Road.

There might always be a faction there dedicated to fighting any British occupation with violence but, now, the IRA graffiti is no longer blending in to parts of the Derry streets, accepted by passers-by. Now, no-one’s numb to it.

For the first time, those messages and their intentions are being challenged

There was once a time when you wouldn’t allow yourself to even think about defacing or just touching anything to do with an IRA symbol or slogan. In Creggan now, in the Bogside, they’re attacking those messages.

Things have changed this week and not in the way that was intended when shots were fired.

The people have risen alright but they’ve risen together in plain sight to condemn the violence.

Now, Up the Ra isn’t so funny anymore.

Now, riots are no longer just a bit of craic.

LISTEN: You Must Be Jokin’ with Aideen McQueen – Faith healers, Coolock craic and Gigging as Gaeilge

RELATED ARTICLES

MORE FROM JOE

MORE FROM JOE