“Tiocfaidh ár bra!”

Sha Gillespie, the queer activist, cried out in joy in Derry’s Guildhall Square. The space outside the landmark building in the Northern Irish city has hosted its fair share of campaigns over the years – some of them hard won, many of them painfully lost.

On Monday night, the city’s walls were draped in banners declaring victory for women and LGBT+ people. Activists were hours away from seeing abortion decriminalised and marriage equality legalised in Northern Ireland. Both achievements had been lifelong ambitions for many activists in Derry.

In that spirit, Ms Gillespie quoted Lyra McKee, the murdered journalist in her speech to pro-choice and LGBT+ activists: “It won’t always be like this, it’s going to get better.”

Rainbow coloured flares were set off from the same city walls. People cried. Some laughed in shock. By midnight on Monday, it had happened.

Northern Ireland, where a mother was almost put on trial for buying abortion pills for her daughter, has now decriminalised abortion completely. No woman will face arrest or prosecution for accessing the health service again. From March, abortion services will be available locally.

It is true that what happened this week was achieved through politics – Wesminster finally showed up for the women of the north; and the DUP didn’t show up at all. But it’s well known that this change never would have happened had those responsible for it not been standing on the shoulders of women who’ve been campaigning for change for at least 30 years, if not more, in Northern Ireland.

Those who felt this day would never come can’t be blamed. There have been plenty of false dawns and even more dark moments over the last few decades.

Flights were booked, bags were packed. Northern Ireland’s pro-choice campaigners were getting ready to go to England, mimicing the same trip taken by thousands of women in the north who need to travel for safe and legal abortion services every year. Northern Ireland’s infamous near-ban on abortion, set down in a Victorian law, was finally about to be lifted through a bill passed at Westminster. A press conference had been planned.

It was the 13th of July, 2008. The day before activists were due to fly to England, Goretti Horgan, the pro-choice campaigner, got a call. Emily Thornberry, the Labour MP who was trying to amend a Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill to extend abortion rights to Northern Ireland, was in tears.

“She was crying on the other end of the phone, I was crying as well,” Ms Horgan said.

It was another major disappointment, and a massive blow to Ms Horgan. Gordon Brown, the then prime minister, had called Ms Thornberry into Number 10. The government at the time had needed the DUP’s support for an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to be able to legally detain ‘terror suspects’ for 42 days. The prime minister explained to Ms Thornberry that pressing ahead with abortion reform from Westminster could jeopardise the peace process.

Ms Horgan, like all abortion campaigners in the north, had heard this before. The Troubles and the peace process had always dominated in Northern Ireland, and left very little space for anything else. In 1998, pro-choice activists had organised an open letter co-signed by some politicians, trade unions and NGOs which pleaded with Westminster not to barter women’s rights for the peace process. Many felt like what played out in the years after had confirmed their worst fears Those fighting for abortion rights in the north had known for a long time that the only people they could truly rely on were themselves.

Despite an attempt by Diane Abbott to salvage abortion reforms for the north shortly after Ms Thornberry’s effort, it would take 11 more years before Westminster would finally pass a law to give women in the north the same rights which women in Britain have had since the 1960s, and which women in the south have had since last January. On July 22 this year, MPs voted to extend abortion rights and marriage equality to Northern Ireland.

Between now and March, the British government will pay the cost of the flights and the abortion procedure for any woman from the north who needs to travel to Britain for a termination. It is expected that from March, abortion services will be available in Northern Ireland, at least up to 12 weeks’ gestation. Terminations for fatal foetal abnormalities and in cases where the life and health of a woman is at risk will be also be available.

JOE understands that that the British government has closely examined Ireland’s abortion law; where a woman can access a termination if she’s less than 12 weeks’ pregnant through pills provided by her local GP. Fears that higher numbers of doctors in the north may refuse to provide terminations, and concerns about the needs of women in more rural parts of the region means that early medical abortion services may be available through pills provided by GPs in the north. Abortion law in England and Wales doesn’t allow this, and requires women to go to an abortion clinic or a hospital. In 2018, 80% of abortions in the UK were performed under 10 weeks’ gestation.

In the days and hours leading up to midnight on Monday, pro-choice campaigners were incredulous. Almost nobody would admit out loud that they were about to succeed, for fear they’d jinx it or see it scrapped at the last minute by DUP “shenanigans.” Activists were texting each other messages of support, and regularly being ambushed by tears whenever they thought about the scale of what was about to happen.

For pro-choice campaigners in the north, this week is the culmination of well over three decades of tireless work which started when abortion rights seemed unpopular, and sometimes impossible.

The first known organised pro-choice protest in Derry was around 1987, but activists had been raising the issue well before then. Many of the women who were campaigning were mothers themselves, and there was always a tension between managing their time and resources between roles. There wasn’t a lot of money around at the time for the cause. Despite this, over the years many of these women have given their own money to help cover the costs of flights and an abortion procedure in the UK for any woman who needed to travel.

In the early days, pro-choice activists tried to raise the issue wherever they could; rather than where was appropriate. Ms Horgan said that they used to go to meetings about various innocuous women’s issues and derail discussions. “We used to go along to these meetings and they might be talking about something like ‘bad dreams,’ and we would somehow bring abortion into it, we were just so determined,” she said.

They were up against it. Ms Horgan said that there was a very specific effect to saying abortion is murder “in a place where people are surrounded by murder – political murder – all the time.”

There’s one anecdote which is shared among the more seasoned pro-choice campaigners, which nobody wanted to have attributed to them for obvious reasons. The INLA, the socialist republican paramilitary group, had its first meeting ahead of it officially forming as a group in 1975. The first topic on the agenda was setting up an army. This ‘army’ went on to kill British soldiers and RUC officers, as well as civilians. At the same INLA meeting, someone raised the issue of abortion rights only to be told in no uncertain terms that the INLA would have nothing to do with “the murder of innocents.”

And Northern Ireland’s laws did treat women who had abortions like murderers. Up until Tuesday, a 158 year old law had made an abortion a criminal offence, punishable by life in prison.

While legal and local abortion services won’t be available in the north until March, the UK government decriminalising abortion on Tuesday is a major success for pro-choice campaigners. It means that whatever happens, abortion will now be a healthcare issue rather than a criminal justice one in Northern Ireland.

Most women will continue to travel to Britain – with flights and the cost of the procedure being covered by the UK government. But as always, some women will self-induce an abortion with pills bought online and taken in secret, in bedrooms and bathrooms across the north.

For the first time, any woman who experiences complications after she’s taken these pills won’t have to worry about being arrested if she goes to a hospital. The British government is anxious to make sure that the public know this, and rightly so.

The fear of being reported to the police is a real one in the north. In 2013, a doctor reported a woman to the PSNI for buying abortion pills online for her then 15-year-old daughter. That woman has only narrowly avoided prosecution. She was due to go on trial in Belfast next month, and was left waiting for midnight on Monday night; when the British government imposed a moratorium on investigations and convictions for illegal abortions in the north. That woman has spent six years worrying about going to jail. In September 2018, she told Amnesty International that the threat of the court case was “there at every important moment of my and my children’s lives, just hanging over me. The fear and pain of it all. I feel like I am not allowed to move on.” The case against her will now be dropped.

Hers is one of a number of cases where authorities in Northern Ireland have decided to prosecute women for accessing illegal abortions, and these decisions have only been taken relatively recently.

In 2016, there was uproar when a 21-year-old woman was given a three month suspended sentence for using abortion pills. The student had been reported to police by her housemates. In response, three women – Kitty O’Kane, then 69, Collette Devlin, 68, and Diana King, 72- handed themselves into a police station in Derry with evidence that they had helped other women to access the illegal pills. The women were daring the authorities to try to prosecute them, to make a show of how archaic the law was.

In 2017, a man and a woman understood to have been a couple accepted a formal caution for using abortion pills. The same year, the PSNI had launched a major crackdown on those who were importing the pills. Two addresses were raided, and at least a dozen people were contacted by the PSNI and invited to come for an interview. It’s not known how many people who ordered the pills have been informally questioned by the PSNI since 2017. JOE unsuccessfully took the PSNI to the Northern Ireland information commissioner to try to access figures on the number of people questioned, but was told in July that the police force had been correct in refusing to release the information under FOI because it would take too long to find and collate the data.

By the time the PSNI decided to crack down on illegal abortion pills, it was well-known that increasing amounts of the drugs were being sent to women all over the island of Ireland. In some cases, a lot of the illegal pills destined for women in the south were being sent to Northern Irish addresses to evade Irish customs, which were regularly seizing the drugs. For years, there has been an all-island underground network of women getting illegal abortion pills to anyone who needs them.

In many ways, the pro-choice movements in the north and the south have always been inextricably linked.When contraception was still banned in Ireland, women’s lib activists travelled to Belfast in 1971 to buy condoms and bring them back on the famous contraceptive train as a form of protest.

The omnipresence of the Troubles and the peace process meant that sometimes, the only time abortion reform could be raised in the north was when it became a major issue in the south. After devolution, the north’s abortion ban became more entrenched and chances of change coming from Stormont seemed slim. Anita Villa, who has been a pro-choice activist in Derry for over 30 years, said she remembers how support for abortion reform in Derry grew following the infamous X Case in 1992. It had emerged that the Irish state had tried to stop a 14-year-old rape victim from travelling to the UK to access an abortion.

“Without that, there was very little chance of the politicians here taking on the issue at all,” Ms Villa said.

She also credits the abortion rights campaign in the south for helping to secure this week’s historic changes. The first time Ms Villa started to believe this might happen for Northern Ireland was the day before the referendum on the Eighth Amendment in the south, when she saw footage of the arrivals hall in Dublin airport. A crowd of young women had gone there to hold banners to welcome everyone who had come home to vote. As women and girls came through the gates wearing Repeal jumpers or Yes badges, cheers would erupt and complete strangers ran into each others harms; hugging, crying or punching the air. Nobody missed how touching it was that an airport – a place which had been so lonely for women who wanted a choice, was now so warm.

“Just seeing those young women, all those young women. And you know, they’re no different from our young women. I realised this is a force that they cannot stop. Those young women: the swell of it, the emotion of all of it. When I saw the footage, it just told me that the tide had turned,” Ms Villa said, and started to cry.

“I’m sorry, I’m sitting here and I didn’t realise I was getting emotional. I just watched what happened in the south and had a feeling that it could happen here. I mean, I’m talking about my granddaughter now. She’s 16. At least her life will be different. At least she will have control.”

The effect that lifting Ireland’s abortion ban would have on the north, where abortion was still banned in most cases, did not come up much ahead of the referendum to repeal the Eighth Amendment in 2018. While it seems obvious now that the vast majority of the Irish public would back abortion reform, it wasn’t always that way. Hypothetical discussions about life after repeal were limited.

This changed quickly on May 26, 2018. It was the day after the referendum, when the votes were still being counted. Two exit polls the night before had projected a landslide victory for the Yes campaign, and early tallies were agreeing. The courtyard of Dublin castle was a cacophony of pure joy and unchecked relief. Hundreds of people, mainly young women, were in such a state of euphoria that anti-abortion campaigners still make bitter reference to “the scenes in Dublin castle” that day. Near the front of the crowd, one woman was holding up a hand-made sign on cardboard which read “THE NORTH IS NEXT.” It was handed to Mary Lou McDonald, Sinn Féin leader and Michelle O’Neill, her deputy, who stood side-by-side on a stage in the courtyard and lifted it between them. A new campaign was created. In the months before the referendum, Sinn Féin had quickly changed its abortion policy to back free access up to 12 weeks so that it could support the new Irish law. This was an all-island policy for the party. Northern Irish anti-abortion activists immediately saw “the north is next” as a threat, those in the courtyard that day viewed it more as a promise.

Irish campaigners had succeeded in using the moment when they were bombarded with international attention – including from the British media – to shift the focus to the north and its Victorian abortion laws.

Now everyone was looking at Northern Ireland, including the Irish government. JOE understands that there were several high-level attempts in Dublin to try to find a way to let women travelling over the border access terminations for free in the republic. This was because the view in the Irish government was there was almost no hope of the north reforming its own laws anytime soon. According to one senior source, the attempt to provide free abortions for women from the north ran into major “legal quagmires.” Simon Harris, the health minister, met with the attorney general and was told that Ireland couldn’t make a health procedure which was not legally available in the north available on the Irish public health service for Northern Irish women.

But despite its good intentions, the Irish government managed to make the new legal abortion services which it introduced in the Republic in January almost useless to women in the north. In attempt to get pro-life members of its own government on board with abortion reform, Fine Gael introduced a mandatory three day waiting period between when a woman first asks for an abortion and a doctor being able to grant it to her. The proposal has been roundly criticised for being misogynistic and medically pointless, and it also made accessing an abortion in the south much more difficult and expensive for women living in the north. Under the Irish law, a woman would have to travel between Derry and Dublin four times for an abortion, between her first appointment and the termination three days later. She would also have to pay over €400. In many cases, it made more sense for women to travel to England or risk ordering abortion pills online. The new Irish law had left them behind.

But some in Westminster wanted to immediately pick up where repeal had left off. Cara Sanquest, an activist with the London-Irish abortion rights campaign, was still watching votes from the referendum being counted in the RDS, Dublin when her phone rang. Stella Creasy, the pro-choice Labour MP, wanted to hire her to help her campaign to extend abortion rights to Northern Ireland. Just over a week later, Ms Creasy would be standing in the House of Commons calling for an emergency debate on decriminalising abortion after the Irish referendum had “thrown a spotlight on the situation in Northern Ireland.”

Ms Creasy had been actively campaigning for abortion rights to be extended to the north from about 2017, which was the same year that the DUP agreed to prop up the minority Tory government after a disastrous general election for Theresa May. The day that news of the deal between the two parties broke, Sky News had a huge screen in studio featuring pictures of all the unionist party’s MPs beneath the giant words “WHO ARE THE DUP?” It’s safe to say that a significant portion of the British public had known little of the anti-abortion, anti-marriage equality DUP before then.

Ms Sanquest said the DUP helped draw attention to Northern Ireland’s abortion laws when they supported Ms May’s government, after their own staunchly conservative views on abortion were highlighted in the British press.

“I think people in England didn’t know much about the DUP, and what they stood for,” Ms Sanquest said. “Well, they do now.”

Building on the work of grassroots activists in the north, Ms Creasy and Ms Sanquest were a key part of a two-pronged strategy to reform Northern Ireland’s abortion laws. The north’s abortion ban was being dragged through the courts, and every successful or failed legal challenge was then being highlighted in Westminster.

In 2017, the Supreme Court ruled against two women who had argued that they should be able to access abortion services on the NHS in England after travelling from Northern Ireland. Immediately afterwards, Ms Creasy tabled an amendment to force the UK government to cover the cost of the procedure for women travelling from Northern Ireland, which it agreed to. The British government also introduced a scheme which would cover the cost of the flight to England for poorer women. (This week, the travel scheme has been extended to all women from the north in lieu of abortion services being available locally.)

The campaign continued. Those who were using the courts wanted to prove that the north’s abortion ban was a breach of human rights, and those using politics wanted to prove that it was Wesminster’s problem.

Abortion might be devolved, but human rights are not. This means that the UK government is responsible for the human rights of women in Northern Ireland. Just two weeks after Ireland’s referendum, pro-choice activists were eagerly waiting for the result of a Supreme Court case which would rule on whether the north’s abortion ban was a breach of human rights. On June 7, the majority of judges in the UK’s highest court agreed that it was, in cases where a woman had been a victim of sexual crime or was carrying a pregnancy diagnosed with a fatal foetal abnormality. But the case was lost, on a technicality. It had been taken by the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission and a mistake in UK law meant that the commission had not had the legal standing to take the case.

In order to count, the case would have had to have been taken by someone whose rights were breached by the abortion ban. In other words, a woman from the north who had been forced to travel. Before the end of the day, Sarah Ewart had decided to do it.

When Ms Ewart was 23-years-old, a devastating 20 week scan revealed that the skull and brain of the baby she was carrying had not developed and meant it was not likely to survive the pregnancy. Because of Northern Ireland’s laws, she had to travel to England to legally terminate the pregnancy which had no medical chance of surviving. Otherwise, she would have to wait until the baby died inside her. She named the baby Ella. The experience of travelling had left her feeling “vulnerable or humiliated.”

A lot of people know this story, because since 2013 Ms Ewart has been forced to tell it over, and over, and over again. Using her own case as a plea to have the law changed, Ms Ewart has re-lived her abortion for journalists, judges, politicians and the public. In the time since she had a termination for medical reasons, Ms Ewart has been pregnant twice more. Both times, she spent her maternity leave lobbying for abortion reform.

“I really don’t think about anyone having to thank me for this, I just knew that what I had to go through was really wrong and I wanted to make sure that any woman and girl out there would never have to do the same thing. I had to do it,” Ms Ewart said.

“I don’t have a grave for my daughter. Maybe now, someone who goes through the same thing will have a grave, or somewhere to visit.”

Ms Ewart resented that what she saw as a healthcare issue was being twisted into a political and religious one in Northern Ireland. For the past six years, Ms Ewart has been campaigning with Amnesty International to change Northern Ireland’s law. It was always clear to her that the change would have to come from Westminster, not Stormont.

One month after Ms Ewart agreed to take another case against the north’s law, there was a major breakthrough in Westminster.

By July 2019, Northern Ireland had been without a government for two and a half years. The British government was forced to introduce a Northern Ireland Bill, to keep the region running in the absence of having politicians in Stormont to do it. This was a major opportunity for Stella Creasy.

Last year, the United Nation’s committee for the elimination of discrimination against women (CEDAW) published a damning report which said Northern Ireland should decriminalise abortion and make it available in cases of rape, incest and fatal foetal abnormality and when the health of a woman – including her mental health – is at risk. Ms Creasy tabled an amendment to the Northern Ireland bill, requiring the UK government to implement the recommendations of the CEDAW report if Stormont wasn’t back up and running by October 21. Conor McGinn, the Labour MP, amended the same bill to legalise marriage equality in the north on the same grounds.

Mr McGinn’s amendment was backed by 383 votes to 73, and Ms Creasy’s was supported by 332 votes to 99.

At home in Northern Ireland, Ms Ewart was watching the vote with Grainne Teggart, the Northern Irish campaign manager for Amnesty International. Both of them burst into tears.

Ms Teggart said this was less because the vote had passed, and more because it had “restored their faith in humanity.”

“It was such a definitive result, clearly showing that Northern Ireland’s laws were wrong. The UK parliament had succeeded in doing what our politicians had failed to,” Ms Teggart said.

But Ms Ewart said she’s beyond being disappointed that her own elected politicians in Stormont were able to help her.

“Where have put so much work and time into this, it’s at a point where I just want change to happen, I don’t care who does it,” she said.

“It’ll be lovely, not to put the past behind me: don’t get me wrong, I’ll never forget my wee girl. But it will be lovely just to put that away, for a while.”

From Tuesday, Ms Creasy’s amendment had worked: abortion has been decriminalised in Northern Ireland. The move has been endorsed by the result of Ms Ewart’s court case earlier this month, which confirmed that the abortion ban was a breach of human rights.

“Today, women can know that their houses will not be raided for abortion pills, they will not be reported to the police if they seek aftercare at the doctors, and they will not be dragged through the courts and threatened with prison just for accessing basic healthcare,” Ms Creasy said.

Ms Creasy said that lifting the threat of prosecution was just the first step towards getting free, safe, legal and local abortion services in the north. A public consultation has now opened ahead of new regulations being put in place in March.

This is a stunning victory for pro-choice campaigners, and a shocking blow for anti-abortion activists.

As recently as last week, pro-life campaigners were still showing up at the doors of DUP politicians beseeching them to do something before Monday. At this point, they knew it would take nothing short of a miracle to stop the abortion ban being lifted.

“But I believe in miracles,” Bernie Smyth, who has been campaigning against abortion for over two decades in the north, said.

Like their pro-choice colleagues, anti-abortion groups had always known that any change to the north’s law could only come from Westminster.

“But we’re probably a bit shocked, and didn’t think it would happen,” Ms Smyth, the founder of Precious Life, said.

Those against abortion had put a lot of faith in the influence the DUP would have in Westminster, now that they were supporting the Conservative government. The irony is that abortion reform likely wouldn’t have happened had it not been for the party’s absence in Stormont.

Anti-abortion groups had pleaded with the DUP to do anything possible to get Stormont back up and running before Monday, including considering giving in to Sinn Féin on the Irish language act. After failing to show up in Stormont after Brexit and the death of Lyra McKee, the DUP went back to the Assembly on Monday to make a show of trying to stop abortion reforms coming in. It was, at best, a stunt and ultimately failed.

Ms Smyth is now vowing to fight back with everything she has, and use every manoeuvre possible to row back any new abortion law in Northern Ireland. When abortion law was liberalised in the south through a popular vote, anti-abortion politicians and campaigners were reluctant to be seen to be doing anything immediately afterwards which could be perceived as not respecting the will of the people.

“We do have an opportunity here that the Republic of Ireland will never be able to have,” Ms Smyth said, adding that she could “never” accept any government or any vote which legalised abortion. Anti-abortion groups are already painting this week’s historic change as something which is being “imposed” by Westminster, which can hopefully be unravelled by Stormont.

But activists like Ms Smyth don’t just have to contend with Stormont anymore. The view in the British government is that because of a slew of judges ruling against the north’s abortion ban, there has to be a human rights compliant abortion law in Northern Ireland “no matter what happens.” And now that abortion has been decriminalised, anyone who wanted to change that back would have to argue in favour of a law that could see women imprisoned. That’s a position that may be too extreme even for the DUP to adopt.

All anti-abortion activists can do now is try to limit access. In Ireland, that’s manifested itself in an increase in rogue crisis pregnancy agencies and “vigils” outside hospitals. It’s a new era for women’s healthcare in Northern Ireland, but it’s a new era for anti-abortion activists too.

Back outside the Guildhall in Derry on Monday, the joy of the campaigners was so potent that it was putting a distinctly rose-coloured tint on the past 30 years.

“Somebody said to me a minute ago, ‘didn’t it come very fast?’” Ailbhe Smyth, the pro-choice campaigner and former co-leader of the Together for Yes campaign, said.

“It did … in the end! But, oh my god. The decades and the decades and the decades and the decades of struggle.”

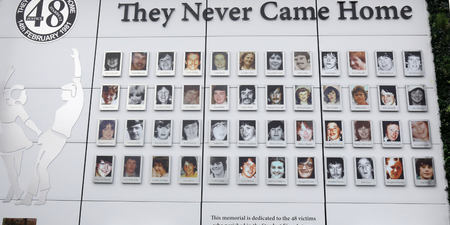

Activists remembered people like Helen Harris and Eileen Blake, who helped found Alliance For Choice in 1997 but have not lived to see this week’s victory. Northern Ireland was commended for being an international beacon of hope, compared to the 11 states in the US which now have almost total bans on abortion and the attempts to row back women’s rights in Poland in Germany.

Campaigners shared stories about women in Derry who were at risk of “going to the bridge,” women who were considering killing themselves rather than continuing a pregnancy.In another case, a woman who needed to go to England had £180 given to her by neighbours in a working class part of Derry.

“We forget sometimes our history, and we forget sometimes all the things we have done throughout the years,” Ms Horgan said.

“From midnight everyone who lives here, will own their own bodies. I wasn’t sure if I’d live to see that day.”

The day is here, the north is now.

LISTEN: You Must Be Jokin’ with Conor Sketches | Tiger Woods loves Ger Loughnane and cosplaying as Charles LeClerc

Topics:

Alliance for choice,Amnesty International,Derry,DUP,Goretti Horgan,Northern Ireland abortion,Sarah Ewart,Sensitive,Stormont,The North Is Next,The North Is NowRELATED ARTICLES

MORE FROM JOE

MORE FROM JOE