Life

Share

26th March 2016

09:43am GMT

1. He was born in Leitrim in 1883. Mac Diarmada hailed from Corranmore, close to Kiltyclogher in North Leitrim. The landscape was dotted with reminders of Ireland's tortured past, including deserted houses and cottages from the mass hunger and emigrations of the 1840s. By the time he had moved to Dublin in 1908 he was already involved in multiple Irish separatist movements; these included the Gaelic League, the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the Ancient Order of Hibernians and Sinn Féin.

2. He was heavily influenced by his father. His father had been a Fenian in Leitrim, a county known to resist authoritarian forces such as landlords, police and troops. McDermott wrote of his father, “It was great to see how hopeful he was of the national cause up to his death, there was something wonderful in the faith of the men of that generation."

This is the statue of Sean Mac Diarmada that stands in Kiltyclogher (credit: Colin Boyle):

1. He was born in Leitrim in 1883. Mac Diarmada hailed from Corranmore, close to Kiltyclogher in North Leitrim. The landscape was dotted with reminders of Ireland's tortured past, including deserted houses and cottages from the mass hunger and emigrations of the 1840s. By the time he had moved to Dublin in 1908 he was already involved in multiple Irish separatist movements; these included the Gaelic League, the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the Ancient Order of Hibernians and Sinn Féin.

2. He was heavily influenced by his father. His father had been a Fenian in Leitrim, a county known to resist authoritarian forces such as landlords, police and troops. McDermott wrote of his father, “It was great to see how hopeful he was of the national cause up to his death, there was something wonderful in the faith of the men of that generation."

This is the statue of Sean Mac Diarmada that stands in Kiltyclogher (credit: Colin Boyle):

3. The seeds of the Rising could be seen as far back as 1910. Mac Diarmada became manager of the radical newspaper Irish Freedom in 1910; a year later were printed the words, "Our country is run by a set of insolent officials, to whom we are nothing but a lot of people to be exploited and kept in subjection. The executive power rests on armed force that preys on the people with batons if they have the gall to say they do not like it."

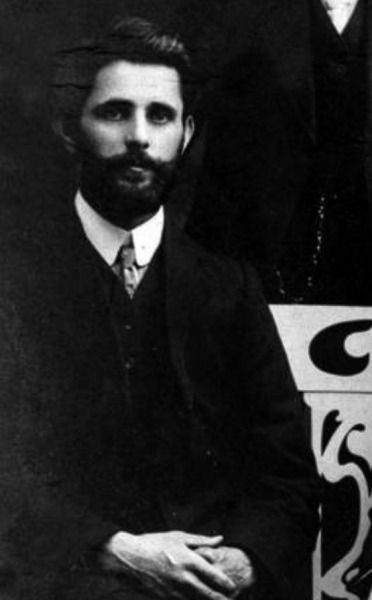

4. His life as a revolutionary began when he met Thomas Clarke in 1907. Together, along with Belfast duo Bulmer Hobson and Denis McCullough, they would oversee the changing of the IRB from the older, more conservative leadership to a younger and more militant idealism, bent on change. He and Clarke would form a close bond personally, and they would become almost inseparable as plans to rebel grew.

5. He was crippled by polio. From 1912 onwards, Mac Diarmada was forced to walk with a cane - he would carry this cane into the G.P.O. during Easter week, 1916.

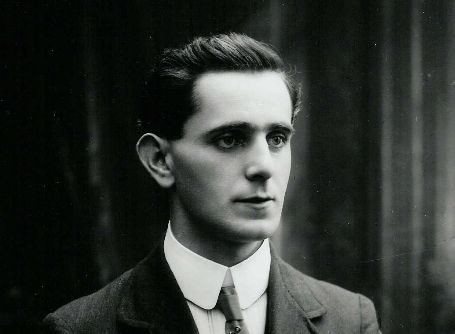

6. He was an early member of Arthur Griffith's Sinn Féin organisation. After an early speech at a Sinn Féin convention in Dublin, he was described as "striking handsome, and earnest, speaking with natural eloquence and with a sincerity which held his audience, gay and light-hearted with a gift of telling a humorous story and a tongue that was witty without being malicious."

3. The seeds of the Rising could be seen as far back as 1910. Mac Diarmada became manager of the radical newspaper Irish Freedom in 1910; a year later were printed the words, "Our country is run by a set of insolent officials, to whom we are nothing but a lot of people to be exploited and kept in subjection. The executive power rests on armed force that preys on the people with batons if they have the gall to say they do not like it."

4. His life as a revolutionary began when he met Thomas Clarke in 1907. Together, along with Belfast duo Bulmer Hobson and Denis McCullough, they would oversee the changing of the IRB from the older, more conservative leadership to a younger and more militant idealism, bent on change. He and Clarke would form a close bond personally, and they would become almost inseparable as plans to rebel grew.

5. He was crippled by polio. From 1912 onwards, Mac Diarmada was forced to walk with a cane - he would carry this cane into the G.P.O. during Easter week, 1916.

6. He was an early member of Arthur Griffith's Sinn Féin organisation. After an early speech at a Sinn Féin convention in Dublin, he was described as "striking handsome, and earnest, speaking with natural eloquence and with a sincerity which held his audience, gay and light-hearted with a gift of telling a humorous story and a tongue that was witty without being malicious."

7. He was arrested in May 1915 under the Defence of the Realm Act. This took place in Tuam, County Galway, as Mac Diarmada was given a sentence of four months' hard labour for sedition, giving a speech urging people against enlisting in the British Army.

8. He fought in the G.P.O. during the rebellion. Along with James Connolly, Pádraig Pearse (whom he disliked personally), Michael Collins and others, Mac Diarmada was among those who stationed on O'Connell Street and it was he that read out Pearse's letter of surrender. When the insurrection was ultimately put down, a British officer sneered at him, "Do the Sinn Féiners take cripples in their army?"

9. He almost escaped execution. He managed to blend in with a large number of prisoners from the G.P.O. until a British officer identified him as 'the most dangerous man after Clarke.' He would ultimately be the last of the rebels to be executed, on the same day as Connolly.

10. His legacy. Sean McDermott Street in Dublin is named after him, as is a railway station in Sligo and a GAA stadium in Carrick-on-Shannon. This plaque is in place outside offices once used by Mac Diarmada.

Previously in this series

James Connolly

Joseph Mary Plunkett

Thomas Clarke

Tomás MacDonagh

Éamonn Ceannt

7. He was arrested in May 1915 under the Defence of the Realm Act. This took place in Tuam, County Galway, as Mac Diarmada was given a sentence of four months' hard labour for sedition, giving a speech urging people against enlisting in the British Army.

8. He fought in the G.P.O. during the rebellion. Along with James Connolly, Pádraig Pearse (whom he disliked personally), Michael Collins and others, Mac Diarmada was among those who stationed on O'Connell Street and it was he that read out Pearse's letter of surrender. When the insurrection was ultimately put down, a British officer sneered at him, "Do the Sinn Féiners take cripples in their army?"

9. He almost escaped execution. He managed to blend in with a large number of prisoners from the G.P.O. until a British officer identified him as 'the most dangerous man after Clarke.' He would ultimately be the last of the rebels to be executed, on the same day as Connolly.

10. His legacy. Sean McDermott Street in Dublin is named after him, as is a railway station in Sligo and a GAA stadium in Carrick-on-Shannon. This plaque is in place outside offices once used by Mac Diarmada.

Previously in this series

James Connolly

Joseph Mary Plunkett

Thomas Clarke

Tomás MacDonagh

Éamonn CeanntExplore more on these topics:

JOE.ie - Life | Joe.ie

life style