It is easy to be misled by our emotions.

When you’re waiting by the side of the road, in the blistering cold or the lashings of rain, anxiety in your stomach over whether or not you’re set to be late for wherever you’re going, a sardine-can bus journey ahead of you, maybe for an hour or more before you reach where you’re going. It’s easy to be consumed by rage.

It’s easy to blame Dublin Bus.

You don’t want to blame yourself, because maybe you are to blame. But the app told you the bus would be here. Still, if you’ve lived in Dublin a while, you should know better by now than to trust the app.

Fool us once. Shame on them. Fool us roughly four times out of five? Then it’s probably our fault for not asking more questions.

Except, people do ask questions. On a daily basis. A cursory search of the Dublin Bus handle on Twitter will show that those who run the organisation’s social media are flat out responding to public interrogations of late, or absent, buses.

There is concrete evidence that Dublin Bus buses do have an uncomfortably high chance of being late.

Figures published by the National Transport Authority (NTA) show that 35 of 112 routes did not hit their targets for any of the 13 four-week periods in 2018. That’s over 31% of all routes. We have nothing to compare this to in terms of whether its an improvement or a deterioration, as it is the first time the NTA has ever made such data public.

The data also showed that 19 routes did meet all their targets for operating on time last year. Which is to say that just 17% of Dublin Bus routes could be trusted to reach their target in terms of punctuality throughout 2018.

It’s also worth noting that in order to meet the target, the majority of buses had only to arrive within five minutes and 59 seconds of their expected time, so even a bus that was nearly six minutes late was still meeting its target. Six minutes is a long time when you’re in a rush – en route to work, a job interview, a date – but by the NTA metric, anything under six minutes late was still “on time”.

me:

Dublin Bus real time information:

— Derek (@DirkVanBryn) April 24, 2019

So let that serve as the empirical back-up for frustrations with the service, which carries approximately 325,000 passengers around the capital every single day, stopping at approximately 5,000 stops.

Any problems with punctuality are compounded by issues with Dublin Bus’ Real Time Information app.

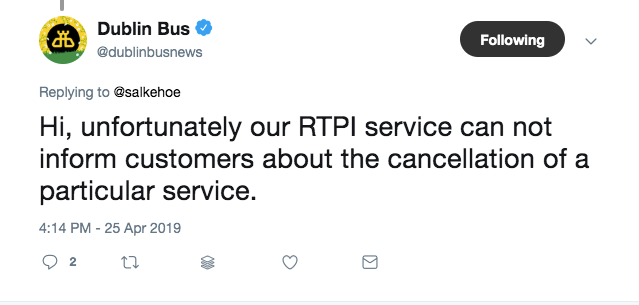

It was confirmed on Twitter last week, by Dublin Bus themselves, that: “Unfortunately, our RTPI [Real Time Passenger Information] service can not inform customers about the cancellation of a particular service.”

After years of struggling, on a personal level, with the mind games of the Dublin Bus app, this short message pushed me over the edge. What? How? What is the purpose of a real time app that cannot alert users to the cancellation of a service?

A key foundation of the Real Time system is that all buses originally appear on the app as ’60 minutes’ away, at 60 minutes before the time they are scheduled to leave the terminus. Immediately, this way of doing things takes variables like traffic out of the equation, and assumes the bus will be at the terminus at the scheduled time.

A spokesperson from Dublin Bus provided JOE with a breakdown of the system: “If the bus assigned has not communicated to a particular board (i.e. doesn’t operate) the first trip on the board will continue to be displayed for all stops within 60 minutes of the trip start time.

“Predictions will continue until the trip is removed from that stop in our system by our team of inspectors in Central Control or the start time of that trip from the terminus has elapsed. This is why a trip may appear for stops close to the terminus, countdown to ‘Due’ but then the bus may not arrive.”

So there are a minimum of two steps here. A bus must communicate that it is not running or running late, first of all, which cannot be counted on. The trip must then be removed by a team of, presumably, very busy inspectors at a different location. So that’s why your bus is showing up on the app even though it’s not on the way, and does not exist.

“For example, a 10.00 Route 25 will be visible on the RTPI section of our app and on RTPI display units from 09.00. This Route 25 trip will continue to show until it’s removed from the system. It may have to be removed for a number of reasons including accidents, diversions or if a service is running late.

“If this is not removed from the system, the Route 25 will continue to display until the departure time of this trip has passed.”

And there you have it. This is not a bug in the system, but a feature of the system. The app is not automated to the degree that a cancelled bus service can be flagged on the spot. It has to pass through at least two human decision-making processes before it’s removed from the app. In the most simple terms, the system works in such a way that inaccurate information is an inevitable by-product.

Similarly, the app struggles to account for buses that are held up in traffic: “When a bus is held in traffic, the predicted arrival time on the RTPI unit will reflect this as it is determined by the bus’ distance between its location and the bus stop and it is not possible to determine the duration of the period of congestion.”

So while your bus could be 10 minutes away, on a busy main road full of traffic, the app could tell you that it is two or three minutes away, based purely on its distance.

And as we know, traffic is not to be trusted in Dublin — a city where cycle lanes, bus lanes and Luas tracks have all been merged into one.

The app hasn’t been updated in over two years now, which means it isn’t built to fit with the the screen-space of the most up-to-date smartphones.

But I am not an app developer, and I can’t speak expertly about the failings of one app or another. In order to fully understand this state of affairs, I reached out to one.

Ben McCarthy is the man behind Obscura and Obscura 2, a camera app with more than a million downloads that has been featured as an Editor’s Choice by Apple.

“Surface more of the information the user needs, without making the user hunt for it. Having a list of favourite stops is handy, but why not show your favourite stops, and nearby stops, on the first screen you see when you open the app?” McCarthy asks.

“This to me is perhaps the biggest disappointment of the app. If the developers of the app really considered the possibilities, there is so much potential for surfacing relevant information. Instead it’s just a whole lot of lists leading you to more lists.

“I’m not even sure what there is to say about the map view. It really feels like the minimum possible effort. Map pins pop in and out of existence as you zoom and move around. When you tap on a stop, the app displays the routes that serve this stop, but no real time info. Why not?”

According to McCarthy, even leaving the Real Time element to one side, the app lacks basic functions now common to high end apps. There is no back-swipe function, allowing users to easily go back to check other routes. Because of this strange navigation process, the app’s display regularly gets scrambled.

There is also no option of dynamic type for users who have impaired vision. Similarly, important buttons, such as the back button, are pushed to the far corners of the screen, making them harder to reach — not least in cold Irish weather, when one’s fingers might be stiff, or the smartphone screen wet.

In 2018, Dublin Bus courted controversy when it was announced that buses would no longer offer change. I mean, it never did, not really. It used to offer change in the form of receipts that could be cashed in at the Dublin Bus HQ. But now, if you don’t have the exact change, you are considered to have “overpaid.” It’s an attempt to nudge people towards buying Leap Cards, but it’s still an almost bemusing stance for a public transport body to take.

Using a Leap Card does cut the user’s fare by a bit, but that’s not to say this deeply flawed service is cheap by any means.

A round-trip that goes beyond 13 stops will cost €5.00, meaning that a lot of Dublin Bus users are paying €25 a week for the service. If we accept this as a bare minimum of a Dublin Bus user’s Dublin Bus usage, you could pay €1,300 annually.

And that’s in addition to the time you lose waiting for a bus that’s not coming — even though the app will tell you that it’s on its way.

It’s real money. It’s real time. Only it’s not.

LISTEN: You Must Be Jokin’ with Aideen McQueen – Faith healers, Coolock craic and Gigging as Gaeilge