We at JOE are building up a list of legendary Irishmen, alive and dead. Joining the list this time is double Olympic gold medallist Dr. Pat O’Callaghan.

By Conor Hogan

Gold medals for Ireland in the Summer Olympic Games are rarities. In fact, in the 19 tournaments the Republic have competed in, they’ve only collected eight. Ireland haven’t managed one in track and field since 1956 and only four in total. Half of those came from one man: one of the greatest hammer throwers the world has ever seen – Dr. Pat O’Callaghan.

Born in Derygallon, Co. Cork in 1906 to Paddy O’Callaghan and Jane Healy, he was the youngest of three sons. An extremely bright child, he began attending national school at the age of only two. Thirteen years later, he won a scholarship at the Mallow Patrician academy and never missed a class. This was despite having to cycle 32 miles every day, from Derrygallon to Mallow and back.

A year later, he earned a place in the Royal College of Surgeons where he studied medicine. When he graduated at the age of 20, he was the youngest medical graduate in the history of Ireland up to that point – in fact, he was too young to practice in Ireland at the time. He was, however, able to serve in the Royal Air Force Medical Corps, where he served until 1928.

The family

The O’Callaghan family were an extremely sporting one – his uncle played Gaelic football for Cork in the 1890s, his brother Sean won a national hurdles title, while his other brother, Con, also represented his country at the Olympics, in the decathlon and in the shot putt. Pat was the most talented of the O’Callaghan clan, however, as he was a runner, thrower, hunter as well as a fine hurler and footballer for two local GAA clubs.

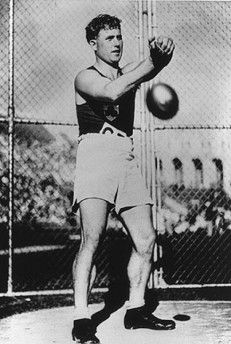

He was introduced to even more sports at college, including rugby and, most significantly of all, hammer throwing. He trained every spare moment he had and even developed his own one with the parts of a bicycle. He won his first national title in 1927 with a throw of 143 feet. He increased that distance by a further 20 feet when he defended the title the following year, before eventually managing 167 feet at the RUC sports in Belfast. This feat earned him a place at Amsterdam ’28.

The Corkonian managed to qualify from the preliminary round at the Olympisch Stadion with a throw somewhat behind his personal best. He started the final in third place and masterfully (and riskily) chose to use the hammer of the leader Oissian Skoeld. The risk paid off, as O’Callaghan broke his own national record and beat the Swede by four inches. He was the first athlete to ever win a medal representing Ireland.

O’Callaghan dominated the Irish athletics scene over the next number of years, consistently winning national titles in the hammer, the shot putt and the high jump. Despite being expected to contend at the ’32 Olympics in Los Angeles, he struggled to get support from the government, the department of health refusing to grant him three months off with pay from work.

“The minister desires to point out that it is undesirable that any officer should be granted prolonged leave at the expense of the rate payers and Dr O’Callaghan should, therefore, be called upon to pay the remuneration of his substitute for the period in excess of his ordinary annual leave,” a statement from the department of health read. He eventually was compensated in March 1933, some six months after the tournament was finished.

A major mix-up hindered O’Callaghan’s preparations severely in Los Angeles. For the first time, the hammer throw was played on a cinder surface, a piece of information the Irish Olympic Committee failed to inform the good doctor. He wasn’t allowed a change of shoe, and his spikes kept getting caught in the surface and as such he struggled to qualify for the final. O’Callaghan managed to get his hand on a hacksaw after it was over and sawed the spikes off his boots.

The Gold Rush

A second throw of 177 feet in the final was enough for him to pick up his second gold medal in a row. Interestingly, he managed this on the same day that Bob Tisdall won the gold medal in the 400m hurdles for Ireland, making it probably the greatest day in the history of Irish athletics.

A dispute between the National Athletic and Cycling (which wanted to have jurisdiction of all 32 counties) and the British Amateur Athletic Association meant that no Irish team competed at the ’36 Olympics in Berlin. He had, the previous December, recorded a throw of 195 feet, more than seven feet longer than the world record then held by fellow Irishman Paddy Ryan, but the British influenced IAAF didn’t recognise it. Not long after the Berlin Olympics, he retired.

O’Callaghan set up his own practice in the town of Clonmel in 1928 at the age of 22, and worked there for a further 56 years. He received the freedom of the town in 1984, the year of his retirement. In his spare time he fished, poached and trained greyhounds. O’Callaghan also remained interested in athletics and attended every games until 1988.

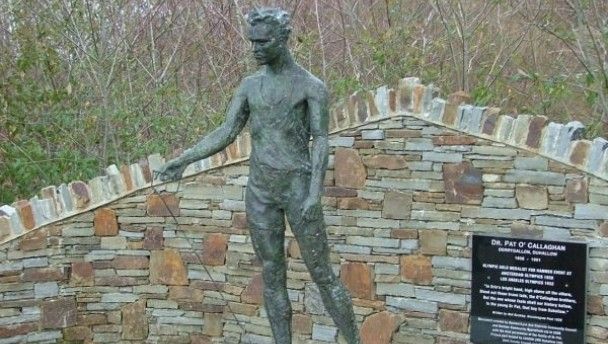

He died in December 1991 at the age of 86, and a statue was erected of him in Banteer, Co. Cork in 2007.

“I would hope this monument would inspire young people to strive for greatness,” his son Dr. Terry O’Callaghan said at the unveiling. “Dr. Pat showed that you don’t have to be born with a silver spoon in your mouth and you don’t have to live in a big city to achieve. Effort and commitment will carry you a long way – it certainly did for Pat O’Callaghan.”

LISTEN: You Must Be Jokin’ with Aideen McQueen – Faith healers, Coolock craic and Gigging as Gaeilge