Share

6th January 2018

06:55am GMT

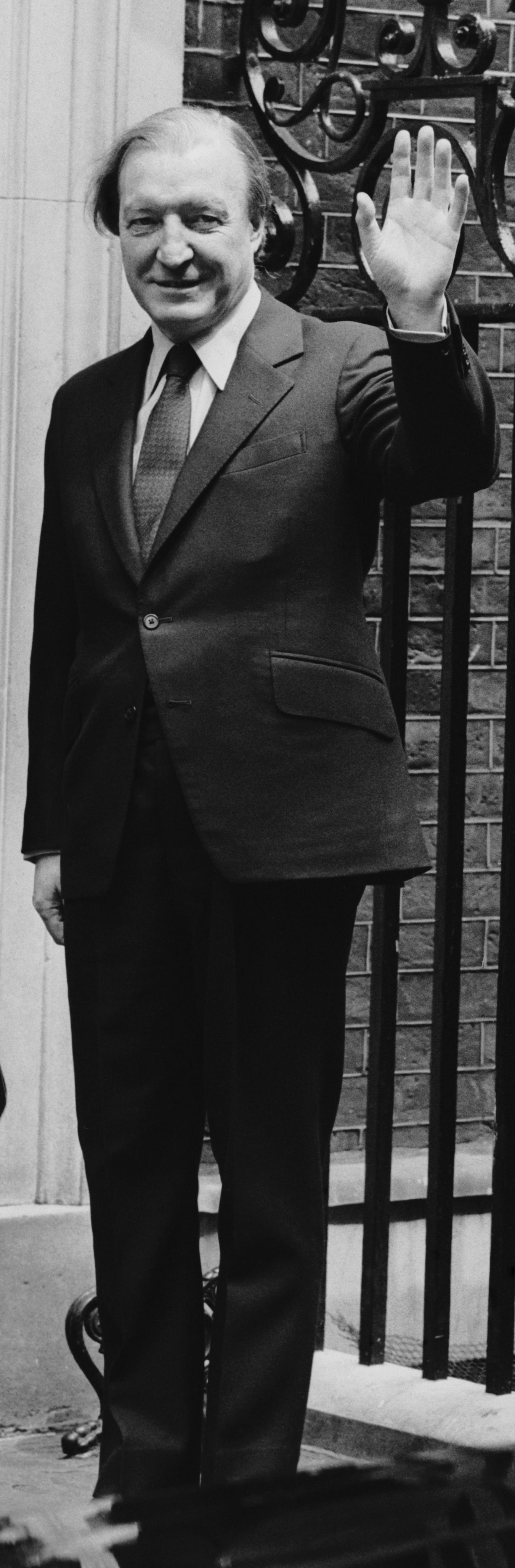

So Haughey stopped and his friend noted that he stayed stopped, as he did, for a time. Except, he added, that during this period of abstinence, Charlie “would break out every now and again”. Given that he was taoiseach or leader of the opposition during the time and undoubtedly under a great deal of strain, this may have been understandable.

When would he break out, I asked, imagining Charlie tying one on every six months or so, reacquainting himself with John Barleycorn after a long absence when he had been wrestling with GUBU or the Gross Domestic Product,.

“Once in a while,” his friend confirmed. “Like at weekends.”

Times have changed and we probably now understand that breaking out ‘every now and again’ doesn’t represent giving up drink in any meaningful sense, but, in its own way, represents the opposite, a renewal of your vows, a determination to make a real go of it this time, but on different terms.

Times have changed and we probably now understand that breaking out ‘every now and again’ doesn’t represent giving up drink in any meaningful sense, but, in its own way, represents the opposite, a renewal of your vows, a determination to make a real go of it this time, but on different terms.

Yet this story may still be familiar to some of us who will have experienced a version of it during long and tortuous negotiations with drink, a negotiating process which can only be successfully completed when one party - and traditionally it’s not alcohol - says, ‘That’s it, you win’.

Until that moment of surrender, we are engaged in some kind of fantasy. The illusion that we, like the Brexiteers in the UK, are capable of taking back control in our relationship with alcohol is one that is hard to resist.

We might break out on weekends, we could drink water with our beer, record our unit intake in a notebook or, an old personal favourite, switch from beer, which we decide is high in toxins, to vodka and freshly squeezed orange juice.

We try and impose some regulation on something which tends to be, if you are a certain kind of drinker, impossible to regulate.All of these things demand a great deal of mental effort, an effort that can lead many to feel that when we aren’t drinking, we’re thinking about drinking, and when we are drinking, we’re thinking about not drinking.

Those who have surrendered tend to experience something different. They tend to discover that the best thing about not drinking is, well, not drinking. With time, the bond you felt was so important looks completely different, a feeling familiar to anyone who has been freed from any kind of obsessive relationship and looks back a few years later and wonders, “What was all that about?”

In that way, they find they are not swearing off, white knuckling or considering their next jailbreak, but experiencing new and strange emotions.

Of course, many do not need to go to such extremes. Those who don't have a problem with alcohol are at liberty to embark on whatever regime they choose, achieving the marginal health gains from their lifestyle choices. But those whose problems are more existential may not necessarily benefit from these extended dry periods.

The advent of Dry January has formalised and regulated the swearing off process that many who had gone on a jag for most of December would have traditionally observed instinctively.

In the past, they might not have felt a great sense of pride at this period of dryness, understanding that it was an essential part of the cycle of a drinker and nothing more.Before Dry January codified it, many would have given this routine a different name. After a bleak Christmas, they might have called it, 'I’m completely fucked' or ‘What the hell is happening with my life?” or, even,'If that fucker can do it, so can I'.

Now it is known as Dry January, a collective pursuit that allows us to experiment with a life without alcohol, safe in the knowledge that this experiment will soon be at an end. Come February, we can break out again, consoled by the assurances that the month has brought some benefits, which we don't need to think about for at least eleven months. Or maybe not until the January after that.

A Dry January may also persuade many that they are on top of the problem - having completed the month, they now have nothing to worry about. Some may also study the latest definitions and suggestions for healthy drinking and bring them to the negotiating table too. It is, for example, recommended that avoiding alcohol for two days every week might be better than staying off it for a month, while binge drinking is now defined by the WHO as three or more drinks in a single sitting. Traditionally, that would only qualify as a binge in Irish terms if the single sitting took place on the bus into work on a Tuesday morning and even then there might have been extenuating circumstances. But this latest definition allows many who would have qualified as a binge drinker under the old regulations to dismiss the whole concept, while anyone who manages to avoid drink for two days a week will assure themselves that there is not a problem.In that sense, these practices and definitions may do nothing to alter the cycle of the drinker, to shift the emphasis in the fundamental way that's required. Because too often there is nothing a person who has a problem with drinking won’t do to avoid confronting the idea that maybe they shouldn’t be drinking at all, even if that includes not drinking for a period of time.

This is why they can often be found engaging in ungodly pursuits like country walks or attending the theatre as they know that there will a drink at the end of it, or even at the interval. More surprisingly, during a time when talking about mental health issues in general is at last more acceptable, there remains a lack of understanding about the mental torment that is a central component for those who have a problem with alcohol.

There remains a widely held view that a person with a drink problem is someone who has lost everything and if they haven't, it isn't a pressing problem, but more of a time management issue.

More surprisingly, during a time when talking about mental health issues in general is at last more acceptable, there remains a lack of understanding about the mental torment that is a central component for those who have a problem with alcohol.

There remains a widely held view that a person with a drink problem is someone who has lost everything and if they haven't, it isn't a pressing problem, but more of a time management issue.

To counter that, some wise people suggest that, instead of swearing off, maybe it's best to ask if your life because of alcohol has become unmanageable and if the answer is yes, take it from there, without further negotiations and trade-offs.

In that way, this torment can be overcome, usually by limiting the amount of time you stay off drink to something manageable, maybe a day, and then trying the same thing the following day, and so on. Of course, it lacks the drama of the grandiose gesture which many with a drink problem are prone to, the sweeping statement that promises that everything is going to change...starting now. But maybe only for a while. Yet many who were addicted to the extravagant pronouncement as well as drink have found that this other way tends to work. What it lacks in excitement, it makes up for in effectiveness. What it is missing in terms of the epic ideas of breaking out every now and again, it makes up for in ways that are harder to define, but sometimes can feel a lot like freedom.Explore more on these topics:

Life Style | Joe.ie

life style