Share

27th July 2019

09:00am BST

JOE: The show has so many different tones - at times it feels like you're watching a horror sequence, other moments are more like a courtroom drama - was that always the intention, and how did you convey that with your VFX work?

Max: We all knew that the story is about people. It's not about the accident, or the technicalities of how it happened. We weren't making a documentary, we were making a TV drama. Everything that we had to do was aimed at supporting the storytelling. We always knew that we had to rebuild the Chernobyl environment which looks so different now than it did in '86. We were very sensitive to that and the reason why we had to take our VFX back to 1986.

We couldn't do modern camera moves, we couldn't do modern grades, we couldn't do a whole raft of things that could have removed the viewer from the drama. On this point, the big thing is that when you look at the show, none of the VFX shots are there for that long. By the time you're thinking 'Oh, this couldn't possibly exist?" you've already moved on in terms of the story.

There was a lot of restraint shown - both in the editing and in the VFX work - just to reign back. One thing I've said since the show aired is that we've treated the VFX as a member of the cast. In that sense, it shouldn't overtake your main actors. You have Jared Harris, Stellan, and Emily Watson. In our minds, seeing Reactor 4 blowing up should never be the main 'actor' in that scene but it is part of the ensemble, it has its place but that place shouldn't be overstated.

This all ties in with the research to make sure that a nuclear scientist could look at this show and say 'that's impossible'. In the same way that Jared Harris' character explains how the reactor exploded, we had to show - in visual terms - how that could plausibly happen.

JOE: The scene where the reactor explodes has so many different beats and layers. What was that like to conceptualise and film?

Max: The most difficult part of that was the conceptual idea. The technicalities of doing it were challenging but manageable. The difficulty with this sort of thing is that you have a lot of shots in there but the people who witnessed them aren't alive anymore. So, how do you know what it's like to look into an open reactor core that's burning at over 7,000 degrees Calvin? How do you know what it's like to be on the roof when the explosion is happening? How do you know what the popping blocks on the biological shield are like?

JOE: The show has so many different tones - at times it feels like you're watching a horror sequence, other moments are more like a courtroom drama - was that always the intention, and how did you convey that with your VFX work?

Max: We all knew that the story is about people. It's not about the accident, or the technicalities of how it happened. We weren't making a documentary, we were making a TV drama. Everything that we had to do was aimed at supporting the storytelling. We always knew that we had to rebuild the Chernobyl environment which looks so different now than it did in '86. We were very sensitive to that and the reason why we had to take our VFX back to 1986.

We couldn't do modern camera moves, we couldn't do modern grades, we couldn't do a whole raft of things that could have removed the viewer from the drama. On this point, the big thing is that when you look at the show, none of the VFX shots are there for that long. By the time you're thinking 'Oh, this couldn't possibly exist?" you've already moved on in terms of the story.

There was a lot of restraint shown - both in the editing and in the VFX work - just to reign back. One thing I've said since the show aired is that we've treated the VFX as a member of the cast. In that sense, it shouldn't overtake your main actors. You have Jared Harris, Stellan, and Emily Watson. In our minds, seeing Reactor 4 blowing up should never be the main 'actor' in that scene but it is part of the ensemble, it has its place but that place shouldn't be overstated.

This all ties in with the research to make sure that a nuclear scientist could look at this show and say 'that's impossible'. In the same way that Jared Harris' character explains how the reactor exploded, we had to show - in visual terms - how that could plausibly happen.

JOE: The scene where the reactor explodes has so many different beats and layers. What was that like to conceptualise and film?

Max: The most difficult part of that was the conceptual idea. The technicalities of doing it were challenging but manageable. The difficulty with this sort of thing is that you have a lot of shots in there but the people who witnessed them aren't alive anymore. So, how do you know what it's like to look into an open reactor core that's burning at over 7,000 degrees Calvin? How do you know what it's like to be on the roof when the explosion is happening? How do you know what the popping blocks on the biological shield are like?

This is all based on sparse eyewitness testimony but to do the explosion, you have to make certain educated assumptions.

For example, the blue glow is based on two different pieces of eyewitness testimony. Craig and Johan were very sure that this effect had to be in the show. But what is that blue glow? We did a lot of research and there's a lot of speculation as to what it was. Some people think it's something that's called the Cherenkov Effect. But what we had in Chernobyl - in the first 15 mins after the explosion - is a thing that's called black body radiation.

It's where matter is so hot that it gives off light. Again, we're looking at the science and examining it. We have an in-house scientist here who did a lot of research here too and although there's no real photographic evidence which definitely says 'it has to look this way' we had to make educated guesses about what it could have looked like. We're making assumptions but they're based on the theoretical science of what happened. This enhances the authenticity of the show and with regards to the blue glow which appears when the Pripyat residents see on 'The Bridge of Death,' they have no idea what they're looking at. They've no idea. Johan said that while these real people are looking on at what's happening and have no idea, our audience should be the exact same, they too should have no idea about what they're looking at.

When the two trainees look down into the open reactor core, again, there's no visual reference for that. Once again, you have to make these educated and scientific assumptions in order to build a language and a visual that if a nuclear scientist looked at that scene, they might think 'well, they probably hit the mark and it's not far off what might happen.' We have evidence that two trainees went up there, but we don't have eyewitness statements of what happened and what it should look like. The show has a lot of these conceptual scenes and getting that visual right and the language correct, that's the main part.

This is all based on sparse eyewitness testimony but to do the explosion, you have to make certain educated assumptions.

For example, the blue glow is based on two different pieces of eyewitness testimony. Craig and Johan were very sure that this effect had to be in the show. But what is that blue glow? We did a lot of research and there's a lot of speculation as to what it was. Some people think it's something that's called the Cherenkov Effect. But what we had in Chernobyl - in the first 15 mins after the explosion - is a thing that's called black body radiation.

It's where matter is so hot that it gives off light. Again, we're looking at the science and examining it. We have an in-house scientist here who did a lot of research here too and although there's no real photographic evidence which definitely says 'it has to look this way' we had to make educated guesses about what it could have looked like. We're making assumptions but they're based on the theoretical science of what happened. This enhances the authenticity of the show and with regards to the blue glow which appears when the Pripyat residents see on 'The Bridge of Death,' they have no idea what they're looking at. They've no idea. Johan said that while these real people are looking on at what's happening and have no idea, our audience should be the exact same, they too should have no idea about what they're looking at.

When the two trainees look down into the open reactor core, again, there's no visual reference for that. Once again, you have to make these educated and scientific assumptions in order to build a language and a visual that if a nuclear scientist looked at that scene, they might think 'well, they probably hit the mark and it's not far off what might happen.' We have evidence that two trainees went up there, but we don't have eyewitness statements of what happened and what it should look like. The show has a lot of these conceptual scenes and getting that visual right and the language correct, that's the main part.

JOE: The helicopter sequence above the open rector core was stunning. What was the ratio of practical effects to VFX on that?

Max: There was a lot of work with that scene! We filmed at Ignalina Power Station which is on the north eastern border of Lithuania and we were given exclusive access to the power station. When Lithuania joined the EC, one of the mandates of joining was that they should decommission this reactor because it's an RBMK reactor - the exact same make and model of the one that exploded in Chernobyl.

In terms of location, it was perfect and we had great access. What we started with was the administration building which were on the outside of he reactors. That's the scene where Jared and Stellan both stand on top of the roof of the buildings. We filmed them just looking at empty sky. What we did thereafter was to put in Reactor 4, build the smoke flume, and add the helicopters. There's a lot of moving parts in that sequence when it comes to building the drama.

The helicopter which crashes, there's real footage of that actually crashing. There's some debate about when it happened and the timeline, but the helicopter crashing did actually happen. Again, it's important to remember that we're telling a story here. This isn't a documentary. That whole scene - we call it the Boron Drop sequence - really started out as a much bigger sequence and it was subsequently paired down by Johan because he wanted to tell the story from the perspective of Legasov because this is his decision. He decided to send the helicopters over, he decided to drop Boron sand over the core.

The story is from his perspective and that gives us context in terms of how to tell the story. All the camera angles - baring two or three - are from Legasov's point of view. Then, we also position a camera in one of the helicopters, in this virtual CG world. Every time you cut to a different camera in that sequence, it's always what I call a legal camera. The camera is either on the ground, or in the helicopter. It's always a POV and using that vocabulary you never take the audience out of the moment.

JOE: The helicopter sequence above the open rector core was stunning. What was the ratio of practical effects to VFX on that?

Max: There was a lot of work with that scene! We filmed at Ignalina Power Station which is on the north eastern border of Lithuania and we were given exclusive access to the power station. When Lithuania joined the EC, one of the mandates of joining was that they should decommission this reactor because it's an RBMK reactor - the exact same make and model of the one that exploded in Chernobyl.

In terms of location, it was perfect and we had great access. What we started with was the administration building which were on the outside of he reactors. That's the scene where Jared and Stellan both stand on top of the roof of the buildings. We filmed them just looking at empty sky. What we did thereafter was to put in Reactor 4, build the smoke flume, and add the helicopters. There's a lot of moving parts in that sequence when it comes to building the drama.

The helicopter which crashes, there's real footage of that actually crashing. There's some debate about when it happened and the timeline, but the helicopter crashing did actually happen. Again, it's important to remember that we're telling a story here. This isn't a documentary. That whole scene - we call it the Boron Drop sequence - really started out as a much bigger sequence and it was subsequently paired down by Johan because he wanted to tell the story from the perspective of Legasov because this is his decision. He decided to send the helicopters over, he decided to drop Boron sand over the core.

The story is from his perspective and that gives us context in terms of how to tell the story. All the camera angles - baring two or three - are from Legasov's point of view. Then, we also position a camera in one of the helicopters, in this virtual CG world. Every time you cut to a different camera in that sequence, it's always what I call a legal camera. The camera is either on the ground, or in the helicopter. It's always a POV and using that vocabulary you never take the audience out of the moment.

First of all, we had to get the flight path of the helicopters correct. That involved an awful lot of work and creative discussions about things like how we need to time the helicopters, at what moment should the first helicopter drop its payload? Secondly, the smoke flume was really difficult because it had to be fully CGI. We had to develop a series of smoke simulations on a computer and the most important thing is that they were plausible. When you look at these things, it had to look real. It couldn't look like a volcanic eruption, or an oil fire. It's understanding the science and context.

What was burning at the time was 800 tonnes of graphite blocks that were still in the reactor chamber. There's a huge thermal updraft of pure carbon that's burning. Then you've got to consider the scale of the scene. How do you mix the speed of the smoke, the texture, the composition, the movement, the colour? Then to have the helicopters coming in and interacting with the flume is another issue. You're building a sequence of little nuanced events that just add and build the tension. The whole sequence was a step-by-step process. We hadn't gone down the big Hollywood route, which is not what Johan wanted to do.

The smoke is challenging because it appears throughout the series and we had to make a timeline of it throughout the five episodes. As the series develops, the fire is gradually put out and smothered, so by the time you get to episode four, there's a daytime view which looks directly down into the reactor core and the fire is basically put out. Every time you cut back to this CGI smoke, it had to look different. The computing time and the R&D time on that was immense because everything had to work chronologically and feel like it would naturally happen, as the story cuts into it at various points.

First of all, we had to get the flight path of the helicopters correct. That involved an awful lot of work and creative discussions about things like how we need to time the helicopters, at what moment should the first helicopter drop its payload? Secondly, the smoke flume was really difficult because it had to be fully CGI. We had to develop a series of smoke simulations on a computer and the most important thing is that they were plausible. When you look at these things, it had to look real. It couldn't look like a volcanic eruption, or an oil fire. It's understanding the science and context.

What was burning at the time was 800 tonnes of graphite blocks that were still in the reactor chamber. There's a huge thermal updraft of pure carbon that's burning. Then you've got to consider the scale of the scene. How do you mix the speed of the smoke, the texture, the composition, the movement, the colour? Then to have the helicopters coming in and interacting with the flume is another issue. You're building a sequence of little nuanced events that just add and build the tension. The whole sequence was a step-by-step process. We hadn't gone down the big Hollywood route, which is not what Johan wanted to do.

The smoke is challenging because it appears throughout the series and we had to make a timeline of it throughout the five episodes. As the series develops, the fire is gradually put out and smothered, so by the time you get to episode four, there's a daytime view which looks directly down into the reactor core and the fire is basically put out. Every time you cut back to this CGI smoke, it had to look different. The computing time and the R&D time on that was immense because everything had to work chronologically and feel like it would naturally happen, as the story cuts into it at various points.

JOE: The big scenes like that one get so much attention and rightfully so. However, I'd imagine that there's a lot of special effects work in smaller moments, moments that the untrained eye wouldn't have seen. Can you tell us about any scenes where we probably didn't notice VFX work?

Clare Cheetham: There was a lot of invisible stuff and most of it had to do with the time period we were recreating. Stuff like painting out the modern elements and changing environments so it looked like we were in 1986. The most challenging stuff were the things that we had no reference for. Scenes like the two guys looking straight into the core and what it looked like. The blue light was another area that we were working from eyewitness accounts and we knew the science behind it, but it was something that nobody has seen.

Max: The show has 846 effects shots in it and these range from your simple clean up on the streets of Lithuania - which doubled as Pripyat - to even taking away stuff like satellite dishes, PVC windows, modern architecture and lighting out of the shot. Another example of these small but seamless uses of CGI is the scene when Dyatlov is down in the bunker and he vomits. That's CGI vomit but again, you wouldn't necessarily know that because some frames are real and some are CGI.

JOE: The big scenes like that one get so much attention and rightfully so. However, I'd imagine that there's a lot of special effects work in smaller moments, moments that the untrained eye wouldn't have seen. Can you tell us about any scenes where we probably didn't notice VFX work?

Clare Cheetham: There was a lot of invisible stuff and most of it had to do with the time period we were recreating. Stuff like painting out the modern elements and changing environments so it looked like we were in 1986. The most challenging stuff were the things that we had no reference for. Scenes like the two guys looking straight into the core and what it looked like. The blue light was another area that we were working from eyewitness accounts and we knew the science behind it, but it was something that nobody has seen.

Max: The show has 846 effects shots in it and these range from your simple clean up on the streets of Lithuania - which doubled as Pripyat - to even taking away stuff like satellite dishes, PVC windows, modern architecture and lighting out of the shot. Another example of these small but seamless uses of CGI is the scene when Dyatlov is down in the bunker and he vomits. That's CGI vomit but again, you wouldn't necessarily know that because some frames are real and some are CGI.

JOE: Do you have a favourite shot that you worked on? Or, a shot that as a member of the audiences, you find the most moving?

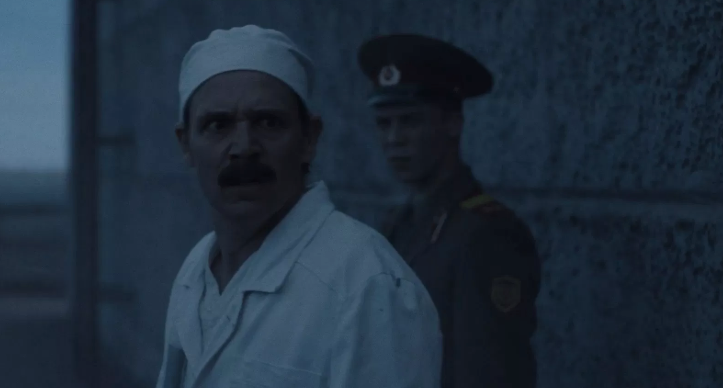

Clare: There's one that stands out for me and that's when Sitnikov walks outside for the first time and you get a sense of the whole vastness of the shot. Then, he looks down into the core and turns back to the camera. There's something really eery about that shot. Other than the wall behind him, everything is completely CG and that moment put a lot of what we were doing together in one scene.

That was one of the first shots where you see the vigour and movement of the smoke. It's quite emotive and prophetic because you know that this poor guy is going to his doom. Again, it's all about the emotional drama of the moment and that remains with him. It's not about the special effects.

JOE: Do you have a favourite shot that you worked on? Or, a shot that as a member of the audiences, you find the most moving?

Clare: There's one that stands out for me and that's when Sitnikov walks outside for the first time and you get a sense of the whole vastness of the shot. Then, he looks down into the core and turns back to the camera. There's something really eery about that shot. Other than the wall behind him, everything is completely CG and that moment put a lot of what we were doing together in one scene.

That was one of the first shots where you see the vigour and movement of the smoke. It's quite emotive and prophetic because you know that this poor guy is going to his doom. Again, it's all about the emotional drama of the moment and that remains with him. It's not about the special effects.

Max: Another one for me was the liquidators on the roof. That's the 90 second sequence when the radioactive rubble has to be cleared by those soldiers on the roof. That was filmed on an exterior stage in a studio that's just outside Vilnius. It's a full blue screen environment. We built the roof and dressed it as close to the original footage as possible. It was all blue screen, so we had to make it feel like we're on top of this roof at around 100 meters up from ground level.

Again, we've got to focus on the drama because that shot has to be exactly 90 seconds and when we were filming that, the main actor in the scene had done his first take and he got all his costume on, but he was absolutely exhausted. This is just on the first take. This gives you a palpable sense of the sacrifices that these people made and there were nearly 4,000 of them going up onto the roof. All they had were these small shovels to chuck this highly radioactive graphite over the roof. Even filming it, you got a sense of the urgency, intensity, pressure, and stress that these people were working under. Again, it's all about the sacrifice and we were very conscious of that.

Max: Another one for me was the liquidators on the roof. That's the 90 second sequence when the radioactive rubble has to be cleared by those soldiers on the roof. That was filmed on an exterior stage in a studio that's just outside Vilnius. It's a full blue screen environment. We built the roof and dressed it as close to the original footage as possible. It was all blue screen, so we had to make it feel like we're on top of this roof at around 100 meters up from ground level.

Again, we've got to focus on the drama because that shot has to be exactly 90 seconds and when we were filming that, the main actor in the scene had done his first take and he got all his costume on, but he was absolutely exhausted. This is just on the first take. This gives you a palpable sense of the sacrifices that these people made and there were nearly 4,000 of them going up onto the roof. All they had were these small shovels to chuck this highly radioactive graphite over the roof. Even filming it, you got a sense of the urgency, intensity, pressure, and stress that these people were working under. Again, it's all about the sacrifice and we were very conscious of that.

JOE: Your work is rightfully receiving so much praise. What does it mean to you personally to say that you're a part of the highest-rated TV show of all time?

Clare: From a personal sense, I've read hundreds and hundreds of scripts and this was one that I read and couldn't put down. I've read some wonderful scripts but when they've gone into production, they've slowly fizzled out and lost some of their impact from the page. This show is the exact opposite. I read the script and fell in love with it. When I saw the original footage come back and how delicately handled the subject matter was, I knew that this was special. The level of empathy from all of the crew and how invested they were was something truly special. That shines through.

Max: All the departments on the show put in a huge effort and that was one of the things that struck me was when I was out in Lithuania last year during filming. We were meeting people who had direct experiences with the disaster and some of these people remember it very vividly. That's important.

It's important to remember that this really happened. People died because of this. There's an inherent honesty and responsibility on the shoulders of everyone that worked on the show. We all felt the need to honour the legacy and accurately convey the central theme of the story, and that's what is the cost of lies? It's important to tell the truth and to be respectful of the memory of what happened.

Chernobyl is available to watch on Sky Atlantic and NOW TV.

JOE: Your work is rightfully receiving so much praise. What does it mean to you personally to say that you're a part of the highest-rated TV show of all time?

Clare: From a personal sense, I've read hundreds and hundreds of scripts and this was one that I read and couldn't put down. I've read some wonderful scripts but when they've gone into production, they've slowly fizzled out and lost some of their impact from the page. This show is the exact opposite. I read the script and fell in love with it. When I saw the original footage come back and how delicately handled the subject matter was, I knew that this was special. The level of empathy from all of the crew and how invested they were was something truly special. That shines through.

Max: All the departments on the show put in a huge effort and that was one of the things that struck me was when I was out in Lithuania last year during filming. We were meeting people who had direct experiences with the disaster and some of these people remember it very vividly. That's important.

It's important to remember that this really happened. People died because of this. There's an inherent honesty and responsibility on the shoulders of everyone that worked on the show. We all felt the need to honour the legacy and accurately convey the central theme of the story, and that's what is the cost of lies? It's important to tell the truth and to be respectful of the memory of what happened.

Chernobyl is available to watch on Sky Atlantic and NOW TV.

Explore more on these topics: