To wear a poppy on the streets of Dublin is as noticeable as not wearing shoes.

It is an instant identifier, an immediate association with Britain and for the time someone wears one, it sets them apart from all those who don’t.

The poppy on our streets and on our clothes looks foreign. Its crimson petals and black centre bring modern debates of Premier League footballers, BBC presenters and apoplectic British tabloids to our minds.

The antiquated debate surrounding ‘to wear, or not to wear’, has been one we could ignore, confident in the south at least that it didn’t have much to do with us.

Misleading

But a tweet sent by one of BBC’s most established journalists, John Simpson, raises a different question: “Irish PM Leo Varadkar wears Irish poppy in Dáil. Until recently Irish politicians have tried to ignore big Irish contribution in both wars.”

While using ‘Irish’ four times in one tweet is impressive, his suggestion that Irish politicians and Irish people have tried to wipe clean the history and honour of the men who died fighting in the First World War is misleading.

But what Simpson inadvertently highlights is that there are established ways of remembering dead soldiers and as the poppy is the symbol the British use, it is the only one they recognise.

While we may excuse ourselves from the wars of poppy fascists and Guardian columnists, the significance of the poppy in Ireland is still laden with meaning. Less than two weeks ago, a war memorial in Sligo was damaged, reportedly because there were poppy wreaths laid at its base, a physical reminder that arbitrary symbols, whether flowers or flags, carry many layers of meaning.

Cuppa tea

When we consider the complicated history of Ireland, where we have come from, how our nation was fought for and won, it is not surprising that the symbols of Britain don’t sit easily with the version of history we’ve been taught and have absorbed.

In Glasnevin Cemetery this weekend, where leaders of the 1916 rising are buried, there was a Remembrance Day celebration and wreaths were lain at the crosses dedicated to the Irish soldiers who fought in both world wars.

Representatives of the Irish government, the French, the Italian, the Canadian and the English, were all in attendance dutifully laying wreaths. And while the ceremony carried the pomp of a military occasion, it was distinctly Irish in tone.

“Jaysis, I can’t wait to get a cuppa tea into me,” said one of the flag bearers, after a long hour of flag-holding and standing erect.

“Days like today are about remembering and hoping these wars will never happen again,” said John Green, Chairperson of the Glasnevin Trust.

But the question lingers; does remembering the international pain and divisions of war really help avoid future conflict?

Written in Blood

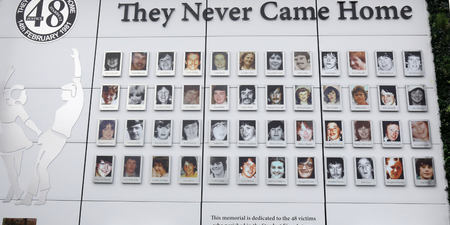

For nearly a century, Ireland has tried to honour the 49,647 Irish men who died in the British forces in WWI. The dilemma over how to do so has existed since the Irish Free State’s nascency.

History is written in the blood of its heroes, and in modern Ireland we have been told our heroes of the early twentieth century are Collins, Pearse, Connolly… the leaders of the 1916 Easter rising, who fought and sacrificed their lives for the idea of an Ireland free of British rule.

How then can Irish people wear the poppy which commemorates the same British forces who in 1916 executed the leaders of the rising, tying James Connolly to a wooden chair to face the firing line as he was too badly injured to stand to his death?

How can we wear a poppy that honours the Black and Tans and the Parachute Regiment who shot 28 unarmed civilians on a 1972 Sunday in Derry during a peaceful protest against internment?

Why should we even consider pinning a poppy that is dyed – figuratively – in the rebel blood of Ireland?

Gaping Wound

It is easy to recall these marks against our geographical neighbours, yet in times of peace, it is a great freedom be able to forget them.

But there is a hole, a gaping wound in our national knowledge of the period between 1914, when the First World War broke out, and 1937 when Eamon De Valera re-wrote the Constitution of Ireland.

A gap which explains why in 1924 over 50,000 Irish people gathered in College Green for Remembrance Day, causing one young republican woman, Elgin Barry – sister of Kevin Barry, who was executed in 1920 for his part in killing three British soldiers – to write of the scene: “There was never anything like the crowd that attended the ceremony. And red poppies, I dream about them now. Really I think we are rather wonderful to have the cheek to think that we could ever have made a republic out of this country.”

This gap is glossed over in the school syllabus, and with it, the experiences of the estimated 150,000 Irish men who fought in the British Army during the First World War were largely kept from the collective knowledge.

Guinness

The reasons these Irish men chose to fight in the British army were diverse. Some were economically motivated, the British forces paid a wage that many living in poverty in Ireland needed, some wanted adventure, and some enlisted on the promise that Ireland would be granted Home Rule if they supported the British forces during the war.

Thousands of boys and men from North and South followed the heralding call of the Irish parliamentary party leader, John Redmond, to go “wherever the firing line extends” and served in the Irish regiments of the British forces.

Public opinion at the time did not see these men unfavourably, many were actively encouraged to go. The Guinness family, one of Dublin’s biggest employers at the time, offered a job for life at the St James’s Gate Brewery for anyone who enlisted in the British Army. They also gave half of the man’s wages to his family while he was away.

Easter Rising

The Ireland these men left was not the one they would return to. While the old guard of John Redmond still sought Home Rule, a new wave of leaders saw Britain’s difficulty as Ireland’s opportunity and the militant nationalism expressed by Eamon De Valera’s Sinn Fein was becoming the dominant ideology for those who sought freedom from British rule.

In France, Greece and Belgium, Irish men were fighting in a bloody and terrible war when they began to get news from home explaining what had happened on Easter Sunday 1916, how the British army, the one they were fighting for, was also the one killing their countrymen on the streets of Dublin. Some men felt they had been ‘stabbed in the back’ , some tried to desert and get back to Dublin to join in, others just kept trying to survive the horrendous conditions of the war.

When these men arrived home after the war’s end nearly 50,000 lives lighter, they came in the uniforms of the British army, a uniform which many then recognised as the enemy’s.

Flanders Poppies

Scarred from a war which was supposed ‘to end all wars’ and many of them suffering with what we now recognise as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, they came to an Ireland that was fighting for independence from the crown they had fought under.

In the years following the end of the First World War, Remembrance Day services were held in churches and cathedrals throughout the country on the weekends preceding the 11th of November. The day King George had named Armistice or Remembrance Day.

The poppy was chosen as the symbol of remembrance as it was the first flower to grow on the battlefields after the Great War ended. On the mornings of the services, hundreds of ex-soldiers of the British forces would march through the streets of Dublin to Phoenix Park, and thousands of people supported them by gathering at College Green.

In 1924, The Irish Times reported that an estimated 40,000 people swarmed the streets of the capital, wearing poppies and singing British military tunes, commenting that “the display of Flanders poppies was not equalled by any city in the British Isles”.

The official figures of poppies sold in Ireland for that same year, as given by the British Legion, was 220,000.

Provocative

Although occasions of mass popularity, the Remembrance Day services and marches were politicised, secularised and divisive. Thousands of people walking through the streets of Dublin in military formation, waving Union Jacks and singing God Save the King, didn’t sit well with an Irish government who was trying to forge a nation of Irish language speakers and Roman Catholics.

The Remembrance Day marches were seen as provocative to the Irregulars, as the IRA were known at the time, and they became events of violence and disorder.

The problem of how to remember the fallen was brewing. At an event on the eve of Remembrance Day 1927, Eamon De Valera stated that ‘nothing was more natural than that men should seek to commemorate the memory of comrades who fought by their side in battle’ but the ‘misuse of the celebration’ could and should be stopped by the police and by citizens ‘making it quite clear that they would not tolerate its continuance’.

Nationalism

And so De Valera and his peers began the idea that has held Irish people ever since, that there is a right way and a wrong way for the Irish to remember those who died in the First World War.

The right way was to honour ‘the young men who went out to France and Flanders because the Nationalist leaders of the time asked them to go’, as expressed by De Valera. The wrong way was to acknowledge not every Irish man signed up for the purposes of nationalism.

The poppy and Irish people’s wearing of it became synonymous with the Union Jack and British imperialism, incongruous with the independent island nation that was emerging on the edge of Europe.

Thus began the long process of trying to remember the dead, politically and culturally, in a way that was cohesive with the new Irish state, a process with which it seems we are still engaging in.

Beheaded

The many contrary layers of the past are encapsulated in MacDonagh station and Casement station and the 13 other railway stations which were named in 1966 after the executed leaders of the 1916 rising. Housed inside these stations are plaques with the names of the Irish who died fighting in the First World War war. You can look for specific names on these memorials through this website.

Politicians have for years been remembering the Irish soldiers of WWI. Mary Robinson, Mary Mac Aleese, Bertie Ahern, John Bruton and Sean Lemass have all commemorated the dead soldiers in different ways.

Where pillars and statues and monuments of British Imperialism have been blown up, beheaded and removed in Dublin, the War Memorial Garden at Islandbridge has remained – despite two separate explosive attacks in the 1950s.

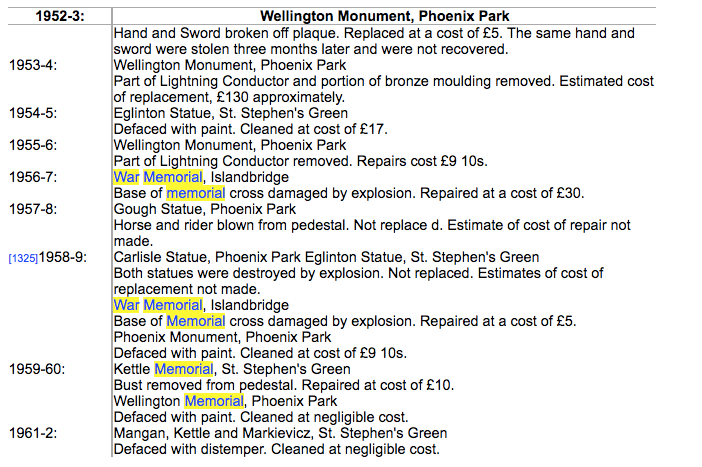

Full list of Damage done to statues/monuments between 1952-1963. Source: Oireachtas.ie.

Leinster House

Last year, The Royal British Legion sold €245,000 worth of poppies in the Republic of Ireland. The money raised from the sales stays in Ireland and goes directly to ex-servicemen and their surviving families.

“We’ve helped some people pay for oil for the winter and we’ve paid off other people’s mortgages,” said Pam Alexander, chairperson of the Dublin Branch of the Royal British Legion (RBL). “Every year I send poppies to Leinster House, but this was the first year a Taoiseach wore one,” she said.

“Practically every Irish person has a relative who fought or died in the First World War,” said Alexander. “The poppy is not a political symbol, but a personal one, you can take whatever meaning you want from it.”

The Royal British Legion has seen an increase of people contacting them in the last five years to find out if they had relatives who fought in the British forces. “The Irish interest in the poppy has spiked once more,” according to Alexander.

British Symbol

2018 will mark the centenary of the end of the Great World War, and whether we as a nation choose to engage with the memories of those who died, why the survivor’s parades were discouraged and why this period was deemed ‘complicated’, is a choice that can only be made with the knowledge of where we have come from.

Perhaps as Irish people, our capacity to forget the rights and wrongs of the past has allowed us greater capacity to explore the present and be open to the future.

The poppy is unavoidably a British symbol, finding out whether we as Irish people want to accept that symbol in part as our own, whether a reimagining of the poppy is needed, or whether we want to consign the past to the past and keep on forgetting, are searching questions, ones that most likely will be forgotten until November 2018, when Remembrance Day is upon us again.

If you’re interested in finding out about family and relatives that died fighting in the British Forces, you can contact the Royal British Legion, Dublin branch here and if your relative was entitled to any service medals the RBL will arrange for copies to made of them for you, free of charge.

LISTEN: You Must Be Jokin’ with Aideen McQueen – Faith healers, Coolock craic and Gigging as Gaeilge