On Friday, 24 hours after Peter Boylan resigned from the board of the National Maternity Hospital, it was reported that the EU was preparing to state that if Ireland unified, Northern Ireland would automatically become part of the European Union.

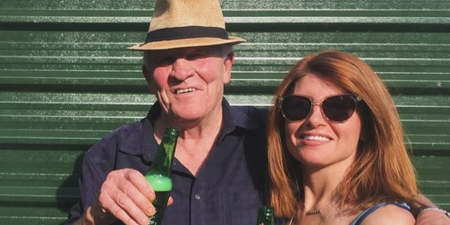

As the former master of the Coombe, Professor Chris Fitzpatrick was resigning from the new NMH project board in support of Dr Boylan and comparing the controversy to dilemmas from Ireland’s past, this idea of a Ireland united in the near future was exciting many.

But the National Maternity Hospital scandal is a reminder of how difficult Ireland finds it to make a break from its past, even as it plans a future hospital for the women and children of the country.

In theory, the fact that Ireland is handing the ownership of a new National Maternity Hospital to an order which historically presided over institutions where some of the most horrendous acts of abuse took place (in a country which had made the abuse of the weak and marginalised a competitive sport) would be a handicap to creating an agreed Ireland which encourages tolerance and diversity.

Fitzpatrick stated in his letter that it was “wholly inappropriate in 21st century pluralist, secular Ireland that the ownership of this publicly funded women and infants’ hospital should be entrusted in any shape, way or form to a religious organisation – of any denomination”. Although given Ireland’s past, it was hardly going to be entrusted to, say, the Seventh-Day adventists.

But maybe that secular Ireland is not the United Ireland people crave. Maybe the 32-county republic will be a place where unionists are welcomed on the basis that they have now seen the light or, post Brexit, they have had no choice but to see the light.

For some, the fact that Northern Ireland tolerates its own absurdism in its health services as laid out in a Newton Emerson column in the Irish Times this week will ensure that Ireland’s curious relationship with the nuns won’t become too much of an obstacle to whatever new Ireland we aspire to.

Whatever the new Ireland is, it will have the same problems as the old Ireland unless there is radical change.

Last weekend, The Citizens’ Assembly delivered strong recommendations for how Ireland needs to progress. As their view became known, it was almost possible to feel sorry for the politicians who will now have to do something, when they must have hoped that coming up with the idea of the assembly in the first place would be the extent of their doing.

Presumably some of them will soon be pressing for the formation of a citizens’ assembly to study the recommendations of the Citizens’ Assembly, but the body once again illustrated how Ireland can’t escape its oppressive past under a constitution designed to enforce it or, at least, designed to do nothing to prevent the oppression.

And still, eighty years on from the constitution coming into force, Ireland is hindered by various aspects of a document which binds the church to the state in many areas of education and health.

Those who are determined that the new hospital is built as quickly as possible are clearly driven by the need to improve the conditions under which women give birth. There is a real danger in the current situation as well, but the solution once again takes Ireland into the land of the absurd.

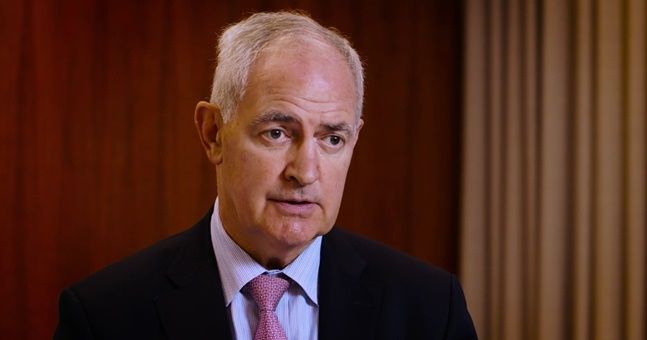

In Peter Boylan’s resignation letter, he laid out the realities when bureaucracy and fundamentalism intersect.

Dr Peter Boylan's letter to the board of the National Maternity Hospital, informing them of his resignation #pknt pic.twitter.com/Fm5sQhrafP

— Pat Kenny Newstalk (@PatKennyNT) April 27, 2017

Boylan told RTE that the issue had become “almost like an episode of Father Ted”. Boylan said the desire to build a new hospital had blinded many on the board to the long-term consequences of the deal. In his letter, one aspect illustrated this strange accommodation.

“All women who will require transfer along the interconnecting corridor into the general hospital for specialist care will be, as you must be aware, transferred into an environment where there is no dispute that Catholic ethos applies.” There is a journey of foreboding and of time travel back to Ireland’s past.

In that overlap, in that corridor, there is room for doubt and concern and historical mistrust.

“What is happening has unfortunate resonances of Dr Noël Browne versus archbishop John Charles McQuaid and the Mother and Child Scheme controversy of the 1950s – and sadly we know how Irish women lost out on that opportunity,” Prof Fitzpatrick said as he resigned his position.

That the row over the National Maternity Hospital has reached a stage where someone is pointing to a moment in Irish history when the power of the church overwhelmed the government should make people reconsider.

Ireland has moved away from those times, perhaps stealthily, but this has been a reminder that the separation may have to be more clearly articulated.

In the 1950s that attempt by the state to change the lives of people it may have naively believed to be its citizens was derailed when the church asserted its power to treat the people as its subjects.

They no longer have that power, but they have influence and wealth which strangely seems to do the same thing.

Boylan follows in a tradition of those like James Deeny, the former chief health officer who was responsible for drafting the Mother and Child scheme in the 1940s before, in 1951, he took the extraordinary step of temporarily closing Bessborough House after he was shocked by the high infant mortality rate. Deeny sacked the matron as well, who happened to be a nun. “The deaths had been going on for a few years. They had done nothing,” he said.

Deeny was a devout Catholic born in Antrim. “Politics, bigotry, intolerance and being on the wrong side of the fence interfered in everything in those days in the north of Ireland,’ he wrote later.

He found a different world in the south. “For the first time I discovered my country. I suddenly felt a free citizen of a free country and began getting the repression and bitterness of the North out of my system.”

The reality may not have been as liberating for Deeny and the reality of Ireland’s liberation has been more disheartening as well. North and south were two competing ideologies engaged in an arms race of intolerance.

The Mother and Baby homes are modern Ireland’s most shameful secret, primarily because so much of what happened was not secret at all but known among communities which did nothing, for many reasons.

Ireland still has to deal with that trauma effectively, to take responsibility for all that happened. To break free from the past, to create that Ireland where women are free from dogmatic intervention – or the fear of dogmatic intervention – will take time and action.

In a rational world, a National Maternity Hospital would not be the battleground in a culture war, but Ireland still has difficulty belonging to the rational world.

LISTEN: You Must Be Jokin’ with Aideen McQueen – Faith healers, Coolock craic and Gigging as Gaeilge