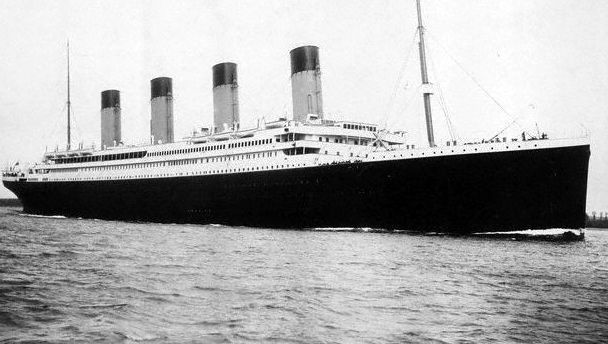

Today marks the 100-year anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic. Marking the occasion, JOE spoke to Rory Golden, the first Irishman to dive to the wreckage and who discovered the ship’s long-lost wheel.

By Mark O’Toole

One hundred years ago today at 11.40pm, the side of the Titanic’s hull careered off an unseen iceberg. By 2.20am the most regal, august and monumental feat of human engineering in history to date had sunk into the frigid Atlantic waters, taking 1,517 out of its 2,223 passengers with it.

The story has been immortalised in countless films and commented on this week by everyone from the President to Jedward. Every one knows what happened… well almost everyone.

It’s undeniable that the story has been imprinted on the collective memory and mythologised to a point where a century later people still care about it.

The Lusitania sank off the coast of Cork with the loss of over 1,000 lives too, precipitating the United States entry to World War 1, while the Titanic’s other gigantic sister ship, the Britannic, went down in the Mediterranean.

Neither commands the same national or international attention as the Titanic, which was built in Belfast and had its final berthing in Cobh, County Cork.

In 2000, Rory Golden became the first Irishman to dive down and see the wreck of the Titanic with his own eyes where it rests 400 miles east of Newfoundland and two-and-a-half miles under the ocean.

Sitting in his Dublin office he muses on why, generations later, we still romanticise and are fascinated by the Titanic.

“It’s a moment caught in time. The ship has so much tragedy and majesty attached to it,” he tells us.

“There were many hopes of the people who were planning to leave Europe to America in the hope of making a new life on a ship making its maiden voyage that for so many reasons never made it.

“It struck a chord with people. The great shock and horror of what happened. This was the epitome of technology of its day and it also showed the lack of care and attention people could have for others’ lives. The lack of lifeboats – the thinking was that the ship itself was a lifeboat and would take so long to sink that other ships in the area could come get them.

“When I first saw the great hull it brought all that home to me – it’s a moment in time.

“When I first cast my eyes on the wreck, for me it was just an incredibly exciting and equally humbling and incredibly poignant moment and you have all these emotions all at once because you are looking at something very few people in the world have seen.”

Rory speaks carefully and reverently about the ship. Both before and after the journey he had an affinity with the ship and a composite knowledge of its making and destruction.

He explains to JOE that the iceberg that was hit was a black iceberg that had turned over so that all the debris and mud from the glacier made it near invisible.

“It didn’t reflect anything off the water, it didn’t glisten, it was a moonless night and a calm sea and the lookouts weren’t on the crow’s nest – all these things combined to make the tragedy

“Even the way she struck the iceberg; one of the ironies, is had the ship struck the iceberg head on it probably would have survived and floated – it was the way it struck her on the side that compromised some water-tight cabins that doomed her.

“The amount of people that died according in proportion to their class and the heroism of those who stayed to get others on the lifeboats. All these things are also memorable.”

Despite his encyclopaedic knowledge of the ship, Rory explains how he nearly didn’t get to go on the dive, despite over 30 years of diving experience.

“I was the first Irish person to dive to it. There were dives from the late eighties when the wreckage was first discovered.

“In late 2000 I was part of an expedition to recover artefacts from the sea bed around the site. My role at the time was to be the dive safety supervisor, but that whole role changed over the course of the expedition.

“There was no guarantee of me going down there because I was very low in the pecking order, but I did bring something with me that ended up being my ticket. That was a memorial plaque that came from Cobh where the Titanic sailed from.

“There was a man down in Cork called Michael Martin, who is a historian who created a walking trip down there called the Titanic Trail. So this was brought with me and the Americans half way through the expedition told me that I would be diving to the ship with this memorial plaque in the basket outside the sub.

“As the Americans said to me, ‘You’re the only Irishman on the sub so you’ve got to go down with it’.”

The pressure in diving four kilometres down to the wreck necessitates an eighteen tonne Russian Mir submarine.

“The life support system on it is only six or seven feet across and three people are crammed into this short space for up to twelve hours and it takes two and a half hours to go down.

“After you lift off and as you move through the ocean your anticipation builds up because the sonar is telling you that you are getting nearer and nearer.

“When you eventually see through to the gloom, looking through a small little porthole and you see this massive wall appearing in front of you, this massive wall of steel.

“The lights come on more full on and you rise up and there you just see the great bow of the ship.”

Seeing the wreckage for the first time

One hundred years has taken its toll, as the pristine jewel and pride of Belfast rusts and decays miles away from the light of the sun and the many human eyes that were once awed by the sight of it. Rory describes the wreck he saw on his first journey to the ship in 2000.

“Well it’s very sad because you are looking at massive decay. The ship broke in two when she sank at the surface. When she ploughed to the bottom she crumpled back on herself.

“You would still recognise the ship, but the stern section is just a massive tangle of debris and it’s a very dangerous area to navigate around in the submarine.

“Yet you still see many parts that you recognise, the bow, the fallen mast, the holes, the steam winches, the anchor chains, the anchors themselves. The wheel-house area is long since swept away though.”

Rory and his colleagues surveyed the wreck and filmed it, taking notes of their observations like previous dives had done.

No one goes in the hull themselves as it’s far too dangerous and only small robotic submarines could ever do that. Rory duly did his duty with the plaque.

“The memorial plaque from Cobh was placed on the bridge and we said a few prayers and took stock of what we had just done because nothing had ever come from Ireland before to be left on the ship.

“Then four years later I was fortunate enough to go back as part of a BBC documentary called A Journey to Remember and we brought plaques from Belfast City Council to commemorate the Belfast people who had lost their lives and also from Harland and Wolff, the shipyard where it was built. We put them either side of the one I had left those year earlier, so it was quite the poignant thing to have done.”

Fortune and luck isn’t something that will ever be associated with the Titanic, but in getting to go down to the ship Rory had been lucky.

Yet before he rose to the surface something else happened, something that elevated Rory’s luck to the realm that would make the fictionalised account of star-crossed lovers Rose and Jack in James Cameron’s blockbuster seem banal by comparison.

Something caught Rory’s eye on his first dive and he deemed it fit for investigation.

“Many other expeditions had been there in the past, but I had seen a small semi-circular piece sticking out of a pile of the debris.

“The robotic arm went in and pulled out, the remains of the wheel, the central brass hub with three stumps wooden spokes hanging out of it and the frame it was mounted in.

“I was the first person to touch that when it got back to the surface. I was the first person to touch the wheel of the ship since it went down in 1912 and probably the last person to hold it before it went down was Captain Smith.”

As well as the day job, since the dive Rory has educated people about the Titanic. One of the things he is anxious to point out is that the ship itself is a memorial to the people who died that night.

“It’s not a mass burial site and I do try to explain that to people. What we have to remember is that fifteen hundred people died because there were not enough lifeboats.

“Most people who died, died on the surface and they died a horrible death. Because they would have been plunged into the water, freezing conditions, and they would have died in ten to fifteen minutes.

“It would have been like people stabbing you with pins and needles and knives such is the shock to system.

“This is what some of the survivors say, that the screams were horrible, but that they died away in a very short period time.

“No bodies were ever found around the area of the wreck site itself, their remains would have been long, long gone. So what I was looking at was a monument to a great tragedy.”

To commemorate the day itself, Rory will be in Belfast at a new commemoration garden that is opening and giving a talk on his dive, yet again keeping the memory alive.

The day will be marked across the world, but with a special reverence amongst the Irish and with the Irishman who recovered that fateful wheel.

[Pic via dipity.com]

LISTEN: You Must Be Jokin’ with Aideen McQueen – Faith healers, Coolock craic and Gigging as Gaeilge