Feargus Callagy runs the only Irish Apnea Academy freediving school in Ireland. He gave JOE a guide to freediving and told us why he finds it so appealing.

By Feargus Callagy

Lying motionless on the surface of the great Atlantic Ocean, I close my eyes. My body rises and falls with the swell that has travelled hundreds of miles before landing at our coast. My right hand holds the line and I take my last breath. I dive down into the green and feel the pressure almost immediately on my ears. I need to equalise my ears over and over the deeper I go.

Finally, I arrive at my chosen depth. Sometimes I close my eyes, sometimes I keep them open. The silence here is extreme. Sometimes all I can hear is my heart beating, gradually getting slower and slower. Other times I hear the rocks on the ocean floor moving around in the swell. I feel a profound sense of peace and well being. A feeling of intensity never experienced above the surface.

After a while, my body – now starved of precious oxygen and being overloaded with carbon dioxide – reminds me I need to breathe. My diaphragm contracts as my body tells me it’s really time to go back now or else we are staying here for good. I move my legs to start finning; the first few strokes are hard as my body is heavy at this depth, as I ascend the effort needed is less and less, until, with six or seven metres to go, I can stop kicking and just float up the rest of the way. At the surface, I exhale slowly and inhale deeply. I am back on the surface yet it all seems different. You have to have a good reason to come back up.

What is freediving?

As humans, we can go weeks without food and days without water but only a few minutes without air. When asked, what is freediving? The simplest explanation I give is that it’s like scuba diving but without the air tanks on your back. It’s a very simple sport where you take your final breath and dive. Because you are not breathing compressed air at depth, you don’t have to worry about decompressing, or the dreaded bends that can affect scuba divers.

I found my way into freediving from scuba diving. I was on scuba for about ten years, but found it restrictive and noisy with a lot of equipment. You don’t realise how noisy it is until you freedive beside a scuba diver. The only fish you see are the ones that want to be seen, but when you’re freediving you can sneak up and surprise them. A lot of freedivers are spearfishermen and hunt in this way for their dinner, but that’s a different tale.

You can try and break down freedivers into a couple of groups: spearfishermen, competitive freediver and recreational freediver. I am not a big fish eater so I rarely spear, but do hunt with the camera in a similar way. A recreational freediver dives to see the marine life and for the experiences they get from diving. A competitive freediver trains and dives in competitions in all or some of the following disciplines.

Constant weight: This is diving as deep as you can finning down and back up and keeping the weight you brought down back up with you. The current record holder is Herbert Nitsch at 124M.

Constant weight no fins: As above, but without the fins, so swimming down and back up breast stroke style. The current record holder is William Trubridge at 95M.

Variable weight: On a sled or weight that drags you down and then you ascend back up with out this weight under your own steam. The current record holder is Herbert Nitsch at 142m.

Static: Holding your breath in the pool while not moving for as long as you can. The current record is held by Stephane Mifsud at 11mins 35 seconds.

Dynamic: Swimming underwater in the pool for as far as possible with fins. The current record holder is Fred Sessa at 255 metres (that’s over 10 lengths of my local pool).

No limits: Due to the dangerous nature of this discipline, it is no longer run at competitions. Athletes can decide to pursue it themselves for the title of world’s deepest. Here you can use a weighted sled to carry you down to your chosen depth and a lift bag to return you to the surface. Unfortunately, several people have died in this discipline over the years. The depths are so great and there is potential for things to go wrong with the equipment or line entanglement. There is very little chance of rescue at these depths.

Free Immersion: This is pulling yourself up and down the line, again maintaining the same weight on your belt at all times. The current record holder is Herbert Nitsch at 120 metres.

While I have competed a few times, it’s always been for the experience and meeting other freedivers and trying out different gear etc. I would regard myself more of a recreational freediver. I love the Ocean, the life and scenery in it. A day’s dive can border on the spiritual for me. The extreme silence experienced is like no other and sometimes the way the light refracts down to the depths is nothing short of mesmerising. The colour, shape and size of our marine life is often stunning, but always beautiful in its own right. This is why I dive.

Breathing

The dives themselves are like a lot of things: easy when you know how. The breathe up prior to the dive is crucial and I teach a technique that utilises more of your lung capacity. As you sit reading this, breathing in and out, you only inhale about half a litre, while your lung capacity could be six or seven litres, so we under utilise them a lot.

The second thing we teach is, when we breathe correctly, our heart rate slows down and our body goes into oxygen conservation mode. The body moves blood away from your extremities like your hands and feet and into your core to be used in the heart, lungs and brain.

What forces us to breathe is not our low oxygen level, but a higher increase of carbon dioxide. This is what sends the message to the brain that we really need to start breathing.

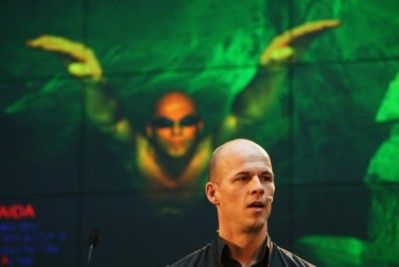

Herbert Nitsch is the holder of a number of free diving records

If we hyperventilate (short, shallow, fast breathing in and out), we blow off a lot of carbon dioxide and trick our body into thinking levels are better than they really are. In this case, we could black out with no warning at all and most probably drown. So here are two handy hints to be written down for ever more: don’t ever hyperventilate and never freedive alone. Are you listening down the back?

Sometimes we have Ocean buddies, i.e. your buddy is over there somewhere and throws his eye on you once in a while. If after two minutes he still doesn’t see you, he may come looking for you but it’s kind of too late at that stage as the diver is probably dead. This scenario is repeated around the world. It’s not ideal, we should be able to see the diver at all times, which can be a struggle with the visibility in Irish waters sometimes.

If in training mode, my arm is attached to the dive line via a lanyard. In the unlikely event of me having a problem, my buddy knows I am somewhere on that line and can either dive down to pick me up or pull back up the line with me attached to it.

Equipment

The human body is amazing and all of us are imbued with what is called the mammalian dive reflex. In essence, when we dive our heart rate slows, our blood shifts to the core, our cells use O2 more efficiently and our spleen contracts, producing more blood cells. The volume is increased and we will feel the need to pee. Now when it comes to peeing at sea there are two types of people: those who pee in their suits and those who say they don’t. I always pee in mine and am always happy to loan a suit out if someone needs it. It is important though to wash your suit carefully after use in freshwater. This brings us on to the specialized equipment.

Probably the most iconic item I use is the long fins or monofins that usually single you out as a freediver rather than a scubie. While monofins are great and people get to try them out on our courses, I find them restrictive for Irish waters. It can be hard to turn with them and they drag in the kelp and seaweed a lot. They are more efficient, however and all the record holders use monofins rather than the traditional long Bi-fins.

In addition to fins, however, I also use a low volume mask. Because I only have the air in my lungs, I can’t use a lot of it to equalise my mask on the descent. Therefore, a mask with a smaller volume is easier to use than a scuba mask. A scuba mask is fine for 10-15 metres, but after that the volume becomes an issue.

The snorkel I use is a simple soft rubber one with a large bore to get as much air in and out of my lungs as I can. I avoid wave and purge chambers as they create a lot of drag on the descent and ascent. Once you dive, always remove the snorkel from your mouth. If you resurface and are close to your limit, that final push to expel the water from the snorkel may cause you to blackout and also allow water to enter the lungs, not a good thing.

Leave it out, get your breath back and then use it again on the surface. Any suit is fine for starting off with, but as you get more into the sport you can acquire specific suits that are more flexible and warmer than surfing suits. Because these suits use open cell neoprene, you need to lube them up to slide in and out of them – always a good conversation opener in any niteclub.

Lastly, I use a rubber weight belt worn on my hips rather than a nylon one around my waist. The reason for this is to allow my belly move in and out while breathing and as I dive down head first the rubber belt stays put, while a nylon belt can easily slip when the suit compresses and move around or slide up to your shoulders.

Getting to know the ocean

Like any sport, we have our own jargon and to overhear two freedivers speaking of their contractions, their neti pots for the sinuses and whether they pack or do negative exhales can be confusing, but it’s a great sport and open to everyone, even if you just want to stay on the surface and look around.

Once you build up your aquacity and are relaxed in the water, you get to know different spots and how they react to the tides and the weather. A good site I use is www.windguru.com for swell and wind predictions and a local set of tide tables or look up easytide for your area.

I have dived in the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, quarries and lakes and still love diving my local green waters of the Atlantic. Sure, the visibility can be terrible at times as can the weather, but it’s my Ocean and is often full of surprises – you just need to search them out a little more.

For more information send me a mail at [email protected], log on to our site at www.freediveireland.com or look us up on facebook at http://www.facebook.com/home.php?#!/FreediveIreland

Enjoy the Ocean and take care of it.