The outstanding documentary is on Netflix and it's definitely worth watching.

Three larger-than-life icons whose immense talents have affected millions. Collectively, their skills have inspired and excited audiences all around the globe. Sadly, the trio have all lived a life that unfolds against a backdrop of controversy and tragedy.

To most people, the lives of Ayrton Senna, Amy Winehouse, and Diego Maradona would have very little in common.

However, to Asif Kapadia, the Oscar-winning director of all three documentaries, his latest film about the Argentinian genius is the final part of a trilogy that has been more than decade in the making.

They might be different people, but to the director, there are narrative similarities throughout the three stories.

As with Senna and Amy, in Diego Maradona, Kapadia reveals the humanity of a genius but in order to do so, the director had to edit through 500 hours of never-before-seen footage from Maradona’s personal archive.

As stated

in our review, the level of access is incredible and the combination of archive material with material is extremely impressive.

Naturally, after the success of Senna and Amy, the director didn't feel the urge to change his stylistic approach.

"The way I'm working to other filmmakers is very different. The way Amy and Senna were put together is the same way that Maradona was put together," said the director when speaking with JOE.

"We're entirely using archive footage and we have his (Maradona's) voice. The construction is quite unusual and it's very personal. It gets quite deep. I guess that he's (Maradona) used to doing quite a lot of TV interviews, which may not have gone as quite deep as we have."

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-qprhPJSysI&feature=youtu.be

While Maradona is definitely a unique individual, Kapadia said that the World Cup winner was a massive fan of the F1 icon, both the man and the 2010 documentary that he made about the three-time world champion.

“He said that he wanted to call his second child Ayrton, if it were a boy. There are photos of him going to Senna’s grave and putting flowers on it. He was a big fan. And as we were researching this I realised that their two stories were running parallel.

"Senna was winning world championships and Diego was winning the title in Italy. And F1 is big in Italy. Whenever we did the research on the sports pages, Ayrton and Diego shared those same pages," said the director.

After being nominated for a BAFTA for his feature length debut, The Warrior, the director's reputation was already on the rise and Senna cemented that further.

An engrossing, nerve-wracking and beautifully crafted examination of a sporting hero, Senna proved to be a massive commercial and critical success. However, Kapadia said that the success of the film gave him another advantage which proved to be absolutely vital throughout his career, creative freedom.

"We're lucky because after Senna, people just said 'we'll let you do your thing.' What I do is I lock myself away. For Maradona, I talked to a lot of people - I interviewed about 80 people for this film from all over the world - and I've got thousands of hours of footage and archive material too."

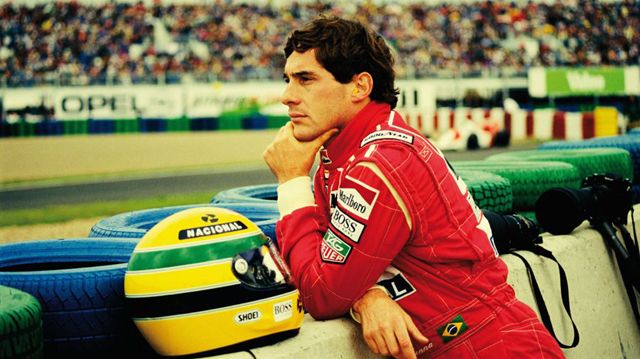

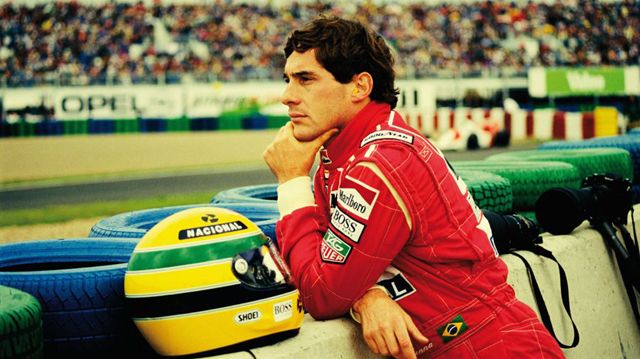

Phenomenally sad yet exhilarating, Senna has rightfully been hailed as one of - if not THE - greatest sports films of all time.

Spanning his years as a Formula One racing driver from 1984 to his untimely death a decade later, Senna explores the life and work of the triple world champion, his physical and spiritual achievements on the track, his quest for perfection and the mythical status he has since attained.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QOQLeqRcgKc

A large reason why the documentary resonated with so many people is that it eschewed traditional documentary techniques in favour of a more cinematic approach that made full use of incredible archive footage, much of which was unseen and drawn from the F1 archives.

In some ways, the narrative arcs that are explored in Senna and Diego Maradona are similar.

For example, both were viewed as gods in their respective countries. Both were remarkably gifted at their sports. Both men became world champions. Both films have a haunting aura of tragedy as the finale approaches.

In terms of their respective personalities, Senna consistently challenged the politics of Formula 1 and was driven by a rivalry to best Alain Prost.

Maradona has always been a street fighter, a player that seemed destined for a collision course with the establishment. Napoli were the perfect fit for him because he was the catalyst that inspired the unfashionable side from Naples to topple the established giants of northern Italy - Juventus, Inter, AC Milan.

In Senna, there's a line that's very telling about the Brazilian driver. During the Japanese Grand Prix, Senna and Prost collide as they both vie for pole position on a tight corner.

"If you no longer go for a gap, you’re no longer a racing driver." The same logic can be applied to Maradona's attitude to football, a game which he describes as "a game of deceit."

Simply put, both men understood that in the pursuit of glory, chances must be taken. It's all or nothing. There are no prizes for second place.

Senna's maverick nature caused tension and battles. Maradona's maverick nature caused tension and battles within himself.

Unlike Senna, the documentary on Maradona covers far more controversial aspects of his personality. For example, the Argentinian's infamous goal against England at the ’86 World Cup, his problems with drugs, ties with the Mafia, and turbulent family life are all highlighted in the film - but both men were masters at their craft.

Aside from the thematic similarities of the documentaries, film fans will know that Kapadia is somewhat unconventional in terms of his aesthetic approach because he doesn't use the traditional 'talking heads' format for a documentary.

"My background is in fiction films and I made quite a few features before I made Senna. They're very visual and have very little dialogue. I'm a fan of pure cinema and I love world cinema, European films, Japanese movies etc.

"For me, the idea is to make films in the style that I want to watch. Making them in the original language is also necessary, so people speak in their own voice and not, sort of, make it easier for English speaking audiences," said Kapadia.

With the rise in popularity of documentary series' on platforms like Netflix, Amazon, and HBO, plenty of filmmakers have embraced the long-form format, however, Kapadia has resisted that urge because he feels that his stories need to be seen by a collective audience.

"For me, the idea came from thinking that these characters are movie stars. Senna is a movie star and he should be seen on the biggest screen available. Amy as well, I want her story to be seen by an audience. Maradona is massive too. I want to be able to see it in Naples, Buenos Aires, Ireland, and all over the world where football is loved and he's known, but with an audience.

"The best way to do that is to make it cinematic, to make it visual. Tell the story with pictures because that's what cinema is. Then when necessary, you can hear a voice but the voice doesn't lead. The voice accentuates, explains, and gives context. That's just my style. Even though my documentaries are personal and my fingerprints are all over them, I try to take myself out of the film."

In terms of the people that are interviewed in his documentaries, Kapadia's decision to not use close-up interviews is grounded in one simple idea, he thinks it's better if the subject tells their own story.

"I want Ayrton Senna to narrate his life. I want Amy Winehouse, or her lyrics, to tell her story. In this case, I didn't want a situation where some great footballer says 'I love Maradona, he was fantastic. I remember that great goal versus England.' Who cares? I'm not interested in that, it's not my style of filmmaking."

While there are thematic similarities in the stories of Senna, Winehouse, and Maradona, the director thinks that the Argentinian's story is very different due to one key aspect, he was frequently his own worst enemy.

"With Senna, he had a very obvious external rival in Alain Prost. With Amy, it was the story of her - her relationship with her family, boyfriend, the media, and fame. With Maradona, it's harder because he achieved so many things but there's no obvious person that was there throughout his life. He didn't really have friends that were there all of his life, but he had some relationships. What was really there, was him.

"Often, if there's no tension or conflict, he creates it. That's where the Diego versus Maradona idea came from. Whatever happens, nobody tells him what to do. He decides what happens, whether it's good, bad, a piece of genius, or a bit of cheating," said Kapadia.

If you've got some free time this week, a double-bill of both films would make for a very interesting watch.

You can watch the Senna on Netflix and Diego Maradona is currently in cinemas across Ireland.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JNaRrDX8MUc

Clips via Altitude Films and Universal Pictures UK

Simply put, both men understood that in the pursuit of glory, chances must be taken. It's all or nothing. There are no prizes for second place.

Senna's maverick nature caused tension and battles. Maradona's maverick nature caused tension and battles within himself.

Unlike Senna, the documentary on Maradona covers far more controversial aspects of his personality. For example, the Argentinian's infamous goal against England at the ’86 World Cup, his problems with drugs, ties with the Mafia, and turbulent family life are all highlighted in the film - but both men were masters at their craft.

Aside from the thematic similarities of the documentaries, film fans will know that Kapadia is somewhat unconventional in terms of his aesthetic approach because he doesn't use the traditional 'talking heads' format for a documentary.

"My background is in fiction films and I made quite a few features before I made Senna. They're very visual and have very little dialogue. I'm a fan of pure cinema and I love world cinema, European films, Japanese movies etc.

"For me, the idea is to make films in the style that I want to watch. Making them in the original language is also necessary, so people speak in their own voice and not, sort of, make it easier for English speaking audiences," said Kapadia.

With the rise in popularity of documentary series' on platforms like Netflix, Amazon, and HBO, plenty of filmmakers have embraced the long-form format, however, Kapadia has resisted that urge because he feels that his stories need to be seen by a collective audience.

Simply put, both men understood that in the pursuit of glory, chances must be taken. It's all or nothing. There are no prizes for second place.

Senna's maverick nature caused tension and battles. Maradona's maverick nature caused tension and battles within himself.

Unlike Senna, the documentary on Maradona covers far more controversial aspects of his personality. For example, the Argentinian's infamous goal against England at the ’86 World Cup, his problems with drugs, ties with the Mafia, and turbulent family life are all highlighted in the film - but both men were masters at their craft.

Aside from the thematic similarities of the documentaries, film fans will know that Kapadia is somewhat unconventional in terms of his aesthetic approach because he doesn't use the traditional 'talking heads' format for a documentary.

"My background is in fiction films and I made quite a few features before I made Senna. They're very visual and have very little dialogue. I'm a fan of pure cinema and I love world cinema, European films, Japanese movies etc.

"For me, the idea is to make films in the style that I want to watch. Making them in the original language is also necessary, so people speak in their own voice and not, sort of, make it easier for English speaking audiences," said Kapadia.

With the rise in popularity of documentary series' on platforms like Netflix, Amazon, and HBO, plenty of filmmakers have embraced the long-form format, however, Kapadia has resisted that urge because he feels that his stories need to be seen by a collective audience.

"For me, the idea came from thinking that these characters are movie stars. Senna is a movie star and he should be seen on the biggest screen available. Amy as well, I want her story to be seen by an audience. Maradona is massive too. I want to be able to see it in Naples, Buenos Aires, Ireland, and all over the world where football is loved and he's known, but with an audience.

"The best way to do that is to make it cinematic, to make it visual. Tell the story with pictures because that's what cinema is. Then when necessary, you can hear a voice but the voice doesn't lead. The voice accentuates, explains, and gives context. That's just my style. Even though my documentaries are personal and my fingerprints are all over them, I try to take myself out of the film."

In terms of the people that are interviewed in his documentaries, Kapadia's decision to not use close-up interviews is grounded in one simple idea, he thinks it's better if the subject tells their own story.

"I want Ayrton Senna to narrate his life. I want Amy Winehouse, or her lyrics, to tell her story. In this case, I didn't want a situation where some great footballer says 'I love Maradona, he was fantastic. I remember that great goal versus England.' Who cares? I'm not interested in that, it's not my style of filmmaking."

While there are thematic similarities in the stories of Senna, Winehouse, and Maradona, the director thinks that the Argentinian's story is very different due to one key aspect, he was frequently his own worst enemy.

"With Senna, he had a very obvious external rival in Alain Prost. With Amy, it was the story of her - her relationship with her family, boyfriend, the media, and fame. With Maradona, it's harder because he achieved so many things but there's no obvious person that was there throughout his life. He didn't really have friends that were there all of his life, but he had some relationships. What was really there, was him.

"Often, if there's no tension or conflict, he creates it. That's where the Diego versus Maradona idea came from. Whatever happens, nobody tells him what to do. He decides what happens, whether it's good, bad, a piece of genius, or a bit of cheating," said Kapadia.

If you've got some free time this week, a double-bill of both films would make for a very interesting watch.

You can watch the Senna on Netflix and Diego Maradona is currently in cinemas across Ireland.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JNaRrDX8MUc

Clips via Altitude Films and Universal Pictures UK

"For me, the idea came from thinking that these characters are movie stars. Senna is a movie star and he should be seen on the biggest screen available. Amy as well, I want her story to be seen by an audience. Maradona is massive too. I want to be able to see it in Naples, Buenos Aires, Ireland, and all over the world where football is loved and he's known, but with an audience.

"The best way to do that is to make it cinematic, to make it visual. Tell the story with pictures because that's what cinema is. Then when necessary, you can hear a voice but the voice doesn't lead. The voice accentuates, explains, and gives context. That's just my style. Even though my documentaries are personal and my fingerprints are all over them, I try to take myself out of the film."

In terms of the people that are interviewed in his documentaries, Kapadia's decision to not use close-up interviews is grounded in one simple idea, he thinks it's better if the subject tells their own story.

"I want Ayrton Senna to narrate his life. I want Amy Winehouse, or her lyrics, to tell her story. In this case, I didn't want a situation where some great footballer says 'I love Maradona, he was fantastic. I remember that great goal versus England.' Who cares? I'm not interested in that, it's not my style of filmmaking."

While there are thematic similarities in the stories of Senna, Winehouse, and Maradona, the director thinks that the Argentinian's story is very different due to one key aspect, he was frequently his own worst enemy.

"With Senna, he had a very obvious external rival in Alain Prost. With Amy, it was the story of her - her relationship with her family, boyfriend, the media, and fame. With Maradona, it's harder because he achieved so many things but there's no obvious person that was there throughout his life. He didn't really have friends that were there all of his life, but he had some relationships. What was really there, was him.

"Often, if there's no tension or conflict, he creates it. That's where the Diego versus Maradona idea came from. Whatever happens, nobody tells him what to do. He decides what happens, whether it's good, bad, a piece of genius, or a bit of cheating," said Kapadia.

If you've got some free time this week, a double-bill of both films would make for a very interesting watch.

You can watch the Senna on Netflix and Diego Maradona is currently in cinemas across Ireland.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JNaRrDX8MUc

Clips via Altitude Films and Universal Pictures UK